Around the World in Many Days, II: Madagascar

Upon landing, it was soon clear that Madagascar was a very different place from the Africa we had left behind.

We came across the first peculiarity even before we left the airport terminal, when we went to an ATM to draw the local currency, the ariary (1 US$ = 3,000 ariary). In a country where more than 90% of the population is extremely poor and lives on less than 9,000 ariary ($3) a day, it possibly makes sense that the highest denomination banknote is a 10,000 ariary note ($3.3). But we as tourists expect to spend about 150,000-300,000 ariary a day ($50 to $100), especially since national park fees are relatively expensive (can easily cost up to 200,000 ariary for two adult foreigners). And since many rural towns do not have any ATMs, and hardly any place accepts credit cards, we knew that we had to stock up a bit, so much so that one day into Madagascar we were already millionaires (1,500,000 ariary = $500), which the mathematically gifted among our readers will quickly calculate to be more than 150 thick bills to carry about, as the highest denomination banknote is a 10,000 ariary note.

Once outside the airport, many more characteristics of the land and its inhabitants were readily noticeable: the deep-red earth that has earned Madagascar the nickname "The Red Island"; the physical features of the Malagasy, that reflect their heritage as descendants of at least three distinct waves of immigration --- first from Malaysia and Indonesia, then from the Arabian Peninsula, and finally from East Africa; the ingrained remnants of French colonialism in the form of language (there are more signs in French than in Malagasy, and almost everyone seems to understand the language, rather than English), culture, cuisine, architecture, and of course herds of Citroen Deux Chevaux taxis galloping through the streets of the capital. And the rest will have to wait for future chapters.

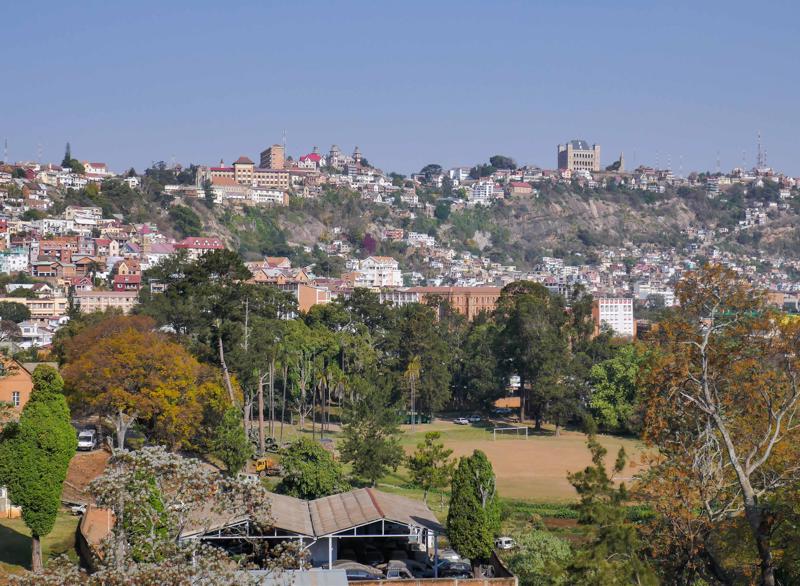

The capital Antananarivo (Tana for short) is a city of contrasts. Built on a steep hill, the rich few live in mansions at the very top, while the miserably poor beg for anything at all but a few hundred metres away. Every street seems packed with cars and people, both precariously sharing the road, yet step through a small gateway into the inner court of a hotel, and you are transported into a sea of tranquility and sophistication that could easily be mistaken to be somewhere in classical Europe. On one corner you may find a girl of ten selling tiny sachets of mango slivers soaked in a bit of lemon juice and salt for 200 ariary ($0.07), while on the next stands a patisserie, seemingly straight out of Paris, offering exquisite pastries, desserts and pralines at 40 times that price, and both are delicious in their own right.

Having booked our first hotel online, sight unseen, we were somewhat surprised to find that it was in fact located in the middle of an impromptu market. Come morning, every inch of sidewalk on both sides of the one-lane street --- for more than a kilometre in each direction --- is overtaken by hucksters, mostly women and children, spreading their merchandise --- be it suitcases or pans or underwear or balls, but especially backpacks and copybooks and covers and labels and pens, for the beginning of the school year is around the corner --- for display, often having it overflow onto the road proper, with potential clients (and a pair of bewildered tourists) walking among the unofficial stalls, as if it were a pedestrian mall, except that, of course, a steady flow of cars is running down the same street, narrowly missing clients, sellers and merchandise, for this is a major thoroughfare of downtown Antananarivo.

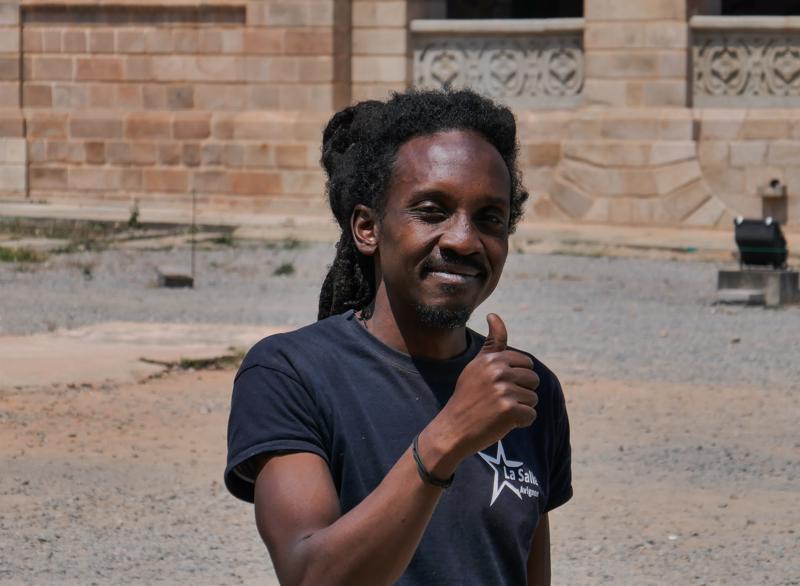

And with this long sentence, it might be time to end this chapter, except that I have as yet failed to mention what we had been doing in Tana in the three and a half days that we spent there. We mostly walked the city, watching and listening, occasionally stopping for a bite from one of the infinite number of small food vendors --- sometimes a tidbit of local cuisine, sometimes one that we were actually able to recognise from back home. As for formal tourist attractions, we visited only two: the historical Rova (the fortress-palace of Queen Ranavalona III, until she was exiled by the French to Algeria in 1896) overlooking the city, which was quite more interesting than we had expected, but not so much because of its buildings and grounds, but rather because of the colourful compulsory guide that took us around the compound --- a local Rastafarian of mixed Malagasy and Ethiopian ancestry called Benjy, who learned his English from an Israeli friend; and the Rova in Ambohimanga (21 km from Tana), a sacred place, which houses two wooden palaces, a traditional one built by an 18th century king, and one European in style built by a 19th century queen --- both quite smaller than you would imagine, the first being only one room, the second three rooms above and two below.

Accommodations:

- Le Logis Hotel (3 nights; very nice room, but the staff was not very knowledgeable)

- Hotel Tana Jacaranda (1 night; the room was not as nice, but the view was great)

Photo captions: (a) What remains of the Tana Rova after the 1995 conflagration that burned away everything wooden; (b) our guide, Benjy; (c-d) Tana from above, looking to the East (residential) and the West (government, industry); (e-f) a shanty town, a stone's throw away from the Tana Rova; (g) King Andrianampoinimerina's palace, Ambohimanga; (h) Queen Ranavalona I's palace, Ambohimanga; (i) the gate to the Ambohimanga Rova; (j-aa) assorted pictures from the city's colourful streets and markets; (bb) the view from our hotel window

R S

11 chapters

16 Apr 2020

[Madagascar] Chapter XV: In which the machine of banknotes disgorges some millions of ariary

Antananarivo and environs, Madagascar, 15-19 Sepember 2017

Upon landing, it was soon clear that Madagascar was a very different place from the Africa we had left behind.

We came across the first peculiarity even before we left the airport terminal, when we went to an ATM to draw the local currency, the ariary (1 US$ = 3,000 ariary). In a country where more than 90% of the population is extremely poor and lives on less than 9,000 ariary ($3) a day, it possibly makes sense that the highest denomination banknote is a 10,000 ariary note ($3.3). But we as tourists expect to spend about 150,000-300,000 ariary a day ($50 to $100), especially since national park fees are relatively expensive (can easily cost up to 200,000 ariary for two adult foreigners). And since many rural towns do not have any ATMs, and hardly any place accepts credit cards, we knew that we had to stock up a bit, so much so that one day into Madagascar we were already millionaires (1,500,000 ariary = $500), which the mathematically gifted among our readers will quickly calculate to be more than 150 thick bills to carry about, as the highest denomination banknote is a 10,000 ariary note.

Once outside the airport, many more characteristics of the land and its inhabitants were readily noticeable: the deep-red earth that has earned Madagascar the nickname "The Red Island"; the physical features of the Malagasy, that reflect their heritage as descendants of at least three distinct waves of immigration --- first from Malaysia and Indonesia, then from the Arabian Peninsula, and finally from East Africa; the ingrained remnants of French colonialism in the form of language (there are more signs in French than in Malagasy, and almost everyone seems to understand the language, rather than English), culture, cuisine, architecture, and of course herds of Citroen Deux Chevaux taxis galloping through the streets of the capital. And the rest will have to wait for future chapters.

The capital Antananarivo (Tana for short) is a city of contrasts. Built on a steep hill, the rich few live in mansions at the very top, while the miserably poor beg for anything at all but a few hundred metres away. Every street seems packed with cars and people, both precariously sharing the road, yet step through a small gateway into the inner court of a hotel, and you are transported into a sea of tranquility and sophistication that could easily be mistaken to be somewhere in classical Europe. On one corner you may find a girl of ten selling tiny sachets of mango slivers soaked in a bit of lemon juice and salt for 200 ariary ($0.07), while on the next stands a patisserie, seemingly straight out of Paris, offering exquisite pastries, desserts and pralines at 40 times that price, and both are delicious in their own right.

Having booked our first hotel online, sight unseen, we were somewhat surprised to find that it was in fact located in the middle of an impromptu market. Come morning, every inch of sidewalk on both sides of the one-lane street --- for more than a kilometre in each direction --- is overtaken by hucksters, mostly women and children, spreading their merchandise --- be it suitcases or pans or underwear or balls, but especially backpacks and copybooks and covers and labels and pens, for the beginning of the school year is around the corner --- for display, often having it overflow onto the road proper, with potential clients (and a pair of bewildered tourists) walking among the unofficial stalls, as if it were a pedestrian mall, except that, of course, a steady flow of cars is running down the same street, narrowly missing clients, sellers and merchandise, for this is a major thoroughfare of downtown Antananarivo.

And with this long sentence, it might be time to end this chapter, except that I have as yet failed to mention what we had been doing in Tana in the three and a half days that we spent there. We mostly walked the city, watching and listening, occasionally stopping for a bite from one of the infinite number of small food vendors --- sometimes a tidbit of local cuisine, sometimes one that we were actually able to recognise from back home. As for formal tourist attractions, we visited only two: the historical Rova (the fortress-palace of Queen Ranavalona III, until she was exiled by the French to Algeria in 1896) overlooking the city, which was quite more interesting than we had expected, but not so much because of its buildings and grounds, but rather because of the colourful compulsory guide that took us around the compound --- a local Rastafarian of mixed Malagasy and Ethiopian ancestry called Benjy, who learned his English from an Israeli friend; and the Rova in Ambohimanga (21 km from Tana), a sacred place, which houses two wooden palaces, a traditional one built by an 18th century king, and one European in style built by a 19th century queen --- both quite smaller than you would imagine, the first being only one room, the second three rooms above and two below.

Accommodations:

- Le Logis Hotel (3 nights; very nice room, but the staff was not very knowledgeable)

- Hotel Tana Jacaranda (1 night; the room was not as nice, but the view was great)

Photo captions: (a) What remains of the Tana Rova after the 1995 conflagration that burned away everything wooden; (b) our guide, Benjy; (c-d) Tana from above, looking to the East (residential) and the West (government, industry); (e-f) a shanty town, a stone's throw away from the Tana Rova; (g) King Andrianampoinimerina's palace, Ambohimanga; (h) Queen Ranavalona I's palace, Ambohimanga; (i) the gate to the Ambohimanga Rova; (j-aa) assorted pictures from the city's colourful streets and markets; (bb) the view from our hotel window

1.

[Madagascar] Chapter XIV: In which we cross the whole of South-East Africa without ever seeing it

2.

[Madagascar] Chapter XV: In which the machine of banknotes disgorges some millions of ariary

3.

[Madagascar] Chapter XVI: In which R does not seem to misunderstand in the least what is said to him

4.

[Madagascar] Chapter XVII: Showing what happened on the voyage from lemur to lemur

5.

[Madagascar] Chapter XVIII: In which a tummy, a taxi-brousse, and a city go each about its business

6.

[Madagascar] Chapter XIX: In which we take a too great interest in water, and what comes of it

7.

[Madagascar] Chapter XX: In which we come face to face with a cliff face

8.

[Madagascar] Chapter XXI: In which the master of the "Kofifi" runs great risk of gaining ariary

9.

[Madagascar] Chapter XXII: In which we find out that, even here, it is convenient to have some money

10.

[Madagascar] Chapter XXIII: In which our pause becomes outrageously long

11.

Summary of Part II and Onwards to Part III

Share your travel adventures like this!

Create your own travel blog in one step

Share with friends and family to follow your journey

Easy set up, no technical knowledge needed and unlimited storage!

© 2025 Travel Diaries. All rights reserved.