Our Chilean Adventure

They slaughtered a baby lamb for us. The night before we got there, they did extra chores so they would be free to spend time with us the next day. This included selecting a three-month-old lamb, slitting its neck, and draining it upside down to make Ñachi or seasoned blood clot jello in the typical Mapuche way. Then they butchered it and got the ribs and lion ready for our visit.

I am reflecting on generosity. Geraldo and I agree, we have never been shown such incredible hospitality in our lives as we did this last weekend -- and we are lucky people who benefit from many, many people's generosity every day. This, though, was something else.

The family I'm talking about lives on a farm near Futrono, a beautiful town on Lago Ranco, about 90 minutes from Valdivia. The Molinas have lived on this farm forever, and their house has five

Ivy Ken

22 chapters

Generosity

Futrono, Chile

They slaughtered a baby lamb for us. The night before we got there, they did extra chores so they would be free to spend time with us the next day. This included selecting a three-month-old lamb, slitting its neck, and draining it upside down to make Ñachi or seasoned blood clot jello in the typical Mapuche way. Then they butchered it and got the ribs and lion ready for our visit.

I am reflecting on generosity. Geraldo and I agree, we have never been shown such incredible hospitality in our lives as we did this last weekend -- and we are lucky people who benefit from many, many people's generosity every day. This, though, was something else.

The family I'm talking about lives on a farm near Futrono, a beautiful town on Lago Ranco, about 90 minutes from Valdivia. The Molinas have lived on this farm forever, and their house has five

humongous tables for big meals, 13 beds, and every kind of crop and animal you can think of. No, actually many you probably can't think of because you, like me, didn't know they exist: murta and murra and mosqueta and membrillo. They have turkeys, chickens, ducks, rabbits, cows, sheep, horses, apples, cherries, strawberries, potatoes, lettuce, tomatoes, onions, and probably two dozen more things.

Just four people do all the work: Señora Florita, the mother and owner, her adult children Panchita and Pirincho, and Panchita's esposo Claudio. From the minute we walked in the door, they cooked, served, showed, and gave to us, all the way up until we drove away with leftovers for lunch the next day.

Let me focus on the meal. The first meal, that is. The table was already set when we got there at 1pm, and we were immediately instructed to sit down, almost even before saying hello to everybody. On the table was salad, homemade bread, potatoes, and wine. But first, Sra. Panchita brought everybody a bowl of fresh chicken soup. She started with Geraldo and quickly, stealthily worked her way around the table. But they all insisted that Geraldo start eating so his soup would not get cold, so he did. You will not be surprised to learn that the soup was delicious. It was buttery with a full chicken piece in every bowl, and Geraldo was instructed to add a little homemade aji chili sauce for flavor, which he happily did.

The minute his bowl was empty, Sra. Panchita cleared it away and Sr. Claudio brought out the main event: the lamb. He had a huge serving tray, and starting with Geraldo again, he served each of our plates full of so. much. meat. I have to repeat it: so. much. meat. The loin was unbelievably tender, and the ribs, flavorful and crunchy-soft. It took me over an hour to eat it. I eat meat regularly, knowing all the excellent reasons not to, but I typically prefer a small few bites of it. There would be no small few bites of this. Even Geraldo, who at times seems like he could eat a side of beef on his own, was overwhelmed by so. much. meat. And of course, wanting to please and honor him, the Molinas kept piling his plate as soon as it got empty. To add to the fun, at least from my vantage point across the table, Geraldo was sitting by the kids who were less able to eat all their meat, so he indiscretely ate all their leftover helpings too.

So. Much. Meat.

Everything on the table, except the wine and the kids' pop, came from the farm. In between bites of meat I devoured the fresh lettuce-tomato-green onion salad and guiltily supplemented with nibbles of buttered bread and boiled potatoes. But they weren't done with us yet, even when all the flesh was gone. Sra. Panchita got up from the table, went to some secret room, and came back with an armful of jars of sweet canned goods. We ate murta que membrillo, which is a mixture of little, tiny, spicy berries and a pear-like fruit that sort of resembles quince. (Because, you know, I eat quince all the time and totally know what it is.) They served this to the adults, and gave preserved cherries to the children. And all through the meal, even though they were eating too, they watched us, wanting everything to be perfect for us. When Geraldo merely looked over at the cherries in the kids' bowls, Sr. Claudio noticed and served Geraldo his own bowl of (very sweet) cherries, which Geraldo ate in addition to his (very sweet) murta/membrillo. There is no chance that before this meal we had any real understanding of the word "stuffed."

Then, in the blink of an eye, the women cleared, washed, dried, and put away the dishes while the men took the kids outside to play fütbol. It was an amazing feat of efficiency that made us feel like we were moving in slow motion while the women flashed around us. They shooed us outside to watch the game, where Srs. Claudio and Pirincho refused to take it easy on the kids on the make-shift field. When it started raining nearly an hour later, they took us for a drive to see some nearby farms and talk about all the rich people from Santiago who buy up farmland without realizing how much work it is to maintain. They would know! While we drove around, the women insisted that

Geraldo go upstairs to nap, and tucked him into one of the perfectly made beds in one of the perfectly tidy rooms.

And then we went back so the kids could ride the horses, chase the chickens, and gawk at the piles of mucho caca. Sra. Panchita walked out of the house at one point with a big bowl of dough, and Srs. Claudio and Pirincho silently stopped what they were doing, escorted her down to a root cellar, and uncovered the wooden rolling machine. Without a word, as though they had done it two

trillion times before, the men assumed their positions on the sides of the machine where they turned the cranks while Sra. Panchita fed large balls of dough through eight times each. I assumed they were busy preparing bread for the week ahead, now that the greedy visitors would soon be on their way. But shortly after, they called us all back into the house where the table had again been set with plates and coffee cups. In the grease on the wood stove floated heavenly little sopapillas. It was time for onces -- sort of a "light," bready dinner chilenos eat after they've already had the huge meal of the day. We ate so. many. sopapillas. And now the Molinas got to display their array of marmeladas, created from all the berries painstakingly picked by Srs. Claudio and Pirincho whose arms are nicked up with thorn scratches year-round. I asked three times what they all were, but my meat-and-bread-induced brain fog prevented me from latching onto the information. I also don’t know what, exactly the sliced gelatinous offering was, but we were told it comes from “the leg.” With homemade garlic mustard sauce on top, it was quite good.

It was late by

now on a Sunday evening, and we still had to drive home. Saying goodbye almost took longer than one of the meals, and their warm, strong hugs made me feel like the prodigal son. Sra. Florita's farewell greeting in particular felt very meaningful, because she had sat and worked all day without smiling or commenting, and I had worried that we had overstayed our welcome and been too loud, too ungracious, too presumptuous, and not good enough eaters. But a stoic face is simply her demeanor, and when each of us approached her for a goodbye kiss, she grabbed us tightly, pressed her soft cheek on ours, and said lots of beautiful words in Spanish that I regret I could not understand. Then she looked us each in the eyes, one-by-one, while holding onto the fleshy parts of

our arms, and smiled into our faces before giving us each another kiss and hug. As we finally made our way out the door after all the goodbyes, Sra. Panchita ran after us with a bag of sopapillas and marmelada de rosa mosqueta for the next day.

Even with all these words, I have not been able to convey the hunger these family members seemed to feel to share their lives with us. The generosity they showed us filled us up, in large part because it seemed to fill them up too. We were happy because they were happy, and they seemed happy because they were able to make us happy. We ate way too much, and got to experience all the good, fun, easy parts of life on a farm (not only with no work on our part, but with naps to boot!).

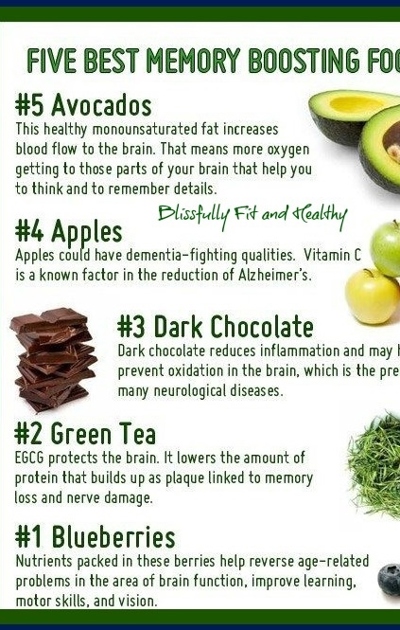

I am grateful for something else, too. This family showed me something different about food than I had understood before. I, like many norteamericanas, tend to think about food as a really personal thing. Every day I think through questions of what I will eat, and what I should and shouldn’t eat. I read articles and labels and books about food, and make decisions about what will be best for me. Maybe these decisions are based on nutrition, or on the politics of the supply chain, or on the labor conditions of the workers who harvest the food that is available to me. Maybe I stop worrying about organic and decide to buy local, or stop worrying about local and buy organic. Either way, I assess my own political stance and my own health status and make decisions about what I believe is best.

And when I get stressed or tired in the middle of the day, I think about taking refuge in a candy bar. As many of my friends know, I have long even kept a secret stash of candy in my office desk drawer for exactly that kind of moment, which I am sorry to say, happens regularly enough that the

secret candy stash has to be replenished much more often than I would like to admit. I don't know if candy is food or not, but let's say it is, and let's imagine this kind of moment along with all the other ways that people enact their relationship with food. I eat candy when I am stressed. It's about me. The phrase, "I'm a vegetarian," to take another example, is also about an individual. "I'm allergic to wheat," is about me. Or, "I'm hungry." Even that simple, basic phrase that does not seem problematic in any way as an expression of a body's alimentary need, is about a single body.

When I was sitting at this huge table of this unbelievably generous family, I couldn't help but to think—and this is pure speculation, maybe even inaccurate, romantic speculation—that there's no individual eating in a family setup like this. When Sr. Claudio is out cleaning the stables at the end of the day and he's tired, I imagine that what he thinks is, "Oh, I can't wait for onces." Maybe he doesn't think about food at all, I don't know. But if he does, maybe he thinks, "I can't wait to sit at the table with everybody, and I'm hoping

that my wife and her mother are in there right now frying dough." I don't think he fantasizes about sitting alone somewhere and having a candy bar. And that was really powerful for me, to think about a group's collectively cultivated relationship to food. They eat as a group. They make decisions about food as a group.

I have no idea what would happen if somebody in this family decided they wanted to eat more broccoli in their diet. Or if somebody in the family read a magazine article that said, "Beta carotene is very important for preventing the loss of eye sight in old age." Maybe they do read those articles. And maybe they have said that to each

other before. And then, what happens? I guess what happens is, everybody starts eating more carrots. Maybe they plant more carrots. But even there, it's a collective thing. It's something they have to, and therefore get to, do together. So it means they have to think about the needs of the group in addition to their own wants and needs. Or probably, the needs of the group constitute their own wants and needs.

I have to believe this allows them or requires them to think about needs in a completely different way than I do. It's all about me, me, me, me, me, for me. And if I'm right, which I might not be, it's all about us, us, us, us, for them. They seem only too happy, as they demonstrated this last weekend,

to include a bunch more people in their "us." So it’s not an exclusionary thing, like a way of enacting a boundary around themselves to keep others out. It’s just not individual.

So, no, I did not want to eat 17 kilos of baby lamb, delicious as it was. And yet, I'm so glad I ate what seemed like 17 kilos of baby lamp on top of 800 sopapillas. I’m glad I got to do this because it made me part of us. It wasn't about anybody's carefully preplanned, individually tailored diet. It wasn’t about anybody’s individual politics. It was part of a group practice, just like holding hands and singing a song would be, or like working together to help a cow birth a calf would be. It was the eating of what was served, and what was available, and what was therefore delicious, that made us an "us." And I shouldn't pass judgment on that, but the truth is, I like it. I don't care that my guts were a little bit bound up the next day. (I am grateful, though, for the shot of homemade vinegar that Sr. Claudio gave me as a way of showing me even more of the farm's production!) They served me

a slaughtered lamb and I liked it. And I liked them. And therefore, I like us.

1.

At the Consulate in DC

2.

Bus Reservations Stress Me Out

3.

Small

4.

Getting What You Asked For

5.

First Days in Valdivia

6.

Ridiculous Goodness

7.

FOOD. primeras observaciones

8.

Temas Fotográficos de Idris: colillas

9.

Our Bearings: they have been found and embraced

10.

A Dad Who Listens

11.

Two words for you: aguas calientes

12.

Temas Fotográficos de Idris: hongos

13.

Time for Poetry

14.

Hiking Parque Oncol

15.

Green Eggs sin ham

16.

When it Rains it Hails

17.

Generosity

18.

The Unique Foods of Southern Chile

19.

Pucón

20.

La Playa

21.

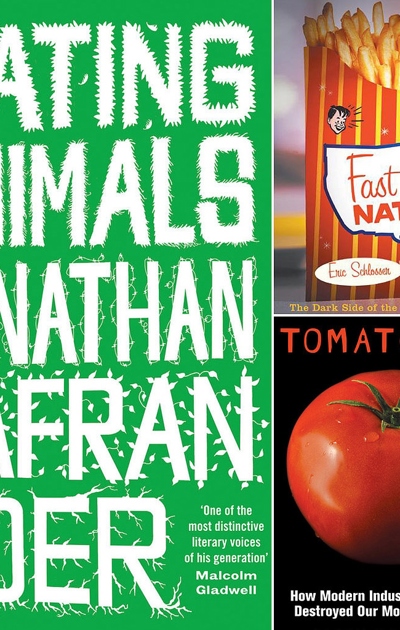

Bonus Book Review

22.

Chile Wrap Up