Saturday October 29, 2016

Shanghai, 29.10.2016

Even though I am really early this morning the ladies are already sitting and waiting for me in the bus; Emily and the driver nod friendly. So I enter quickly and while the bus drives to the station I eat some toasted bread and bananas from the breakfast bags I received.

It is 5:30 a.m. The traffic is loud and the sky is grey in the early morning of Hangzhou. It has been wonderful to have visited this city situated at the West Lake; it is a place full of history and it will have a strong future.

We arrive at Hangzhou’s modern train station; we receive our train tickets from Emily; and then she says goodbye leaves us behind. We are with four now: Truke, Christine, Bente and me. We enter the big hall and wait for the speed train to Shanghai to arrive. I take a selfie. On wide screens appears an advertisement for a brand of tea (and by the way you are captured on camera for security reasons while looking at the screen) – is this underglaze or overglaze enamel I ask myself, while looking at the tea-cup on the screen.

The speed train arrives. The gates to the train do not let me pass when I put my ticket on the scanner. Bente calls out to a guy in the queue: “go with her through the gates!” For some reason he obeys to this “command”and we pass through the gate together. In the train Christine sits next to me; Bente and Truke sit behind us. In 90 minutes we will arrive in Shanghai. Christine does so many Oriental art studies and has so many contacts that I am still kind of shy, with my lack of knowledge, to sit next to her; but she gives me a cracker and is very kind. She tells me about Shanghai: “In Shanghai not many people speak English” and then she gives me tips and tricks to still find my way in the city.

I think of Lin Shu, a Chinese scholar of the 19th century who did not speak English either but, with the help of others, still managed to introduce English (and French) literature to the general public. Similarly, I will have to find my way in Shanghai by asking others to translate instructions which read in English into Chinese characters, and then show them to taxi drivers for example.

Behind me in the train I hear Bente and Truke chatting. They will travel onwards to Taipei, to visit the National Palace Museum in

Taipei. I was there during an earlier trip with my father and another VVAK group in Taipei so I know they will see a beautiful collection. My cold is getting worse I must be careful not to infect the others, although there are many travellers sounding like they have a cold as well.

The train rides through the outskirts of Shanghai with industries poisoning the city population. Like in many cities in China, the air is polluted. A transparent but black veil of dust covers the flowing landscape of this Yangtze delta. In 1712 Pere d’Entrecolles, a Jesuit missionary, described in his letters to the mission team at home in France, his visit to Jingdezhen; at the time that town was suffering from an ash grey sticky dust and black charcoal fumes too.

In the train I read a Wikipedia page on Shanghai. It points out that the western world brought a lot of luck to the city.:“Shanghai is the most populous city in the world, with a population of more than 24 million as of 2014. It is one of the four direct-controlled municipalities of China. It is a global financial centre and transport hub. The world's busiest container port is located in the Yangtze River Delta in East China. Shanghai sits on the south edge of the mouth of the Yangtze in the middle portion of the eastern Chinese coast. The municipality

borders the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang to the north, south and west, and is bounded to the east by the East China Sea.

As a major administrative, shipping and trading city Shanghai grew in importance in the 19th century due to trade and recognition of its favourable port location and economic potential. The city was one of five treaty ports forced open to foreign trade following the British victory over China in the First Opium War. The subsequent 1842 Treaty of Nanking and 1844 Treaty of Whampoa allowed the establishment of the Shanghai International Settlement and the French Concession. The city then flourished as a centre of commerce. After the Opium war Shanghai became the commercial and industrial capital of China. It became the centre of trade between China and other parts of the world (predominantly Western countries), and became the primary financial hub of the Asia-Pacific region in the 1930s.

Despite all this “luck”, Shanghai’s history has been complicated and tough, of course. I have read about the appalling impact of the Opium Wars in books such as “Les Français en Chine” by Jean de la Guèriviere.

The train arrives at Shanghai Central station; we are on the platform already; we roll our luggage towards the exit. We need to show our

tickets to the station guard to exit through the platform gates. Truke, Christine and Bente have already passed those gates. I lost my ticket somewhere in my bag: the guard politely looks the other way when he lets me pass the gate without showing the required ticket to him. In my back pocket I find the ticket. In the big station hall I hold it up from a distance to the guard who let me pass the gate: he does not react. During our trip not very often a conflict between people is visible – not in the streets or outside anywhere; is it the influence of Taoism? Or is “all emotion hidden”? Is it the influence of the state? Suddenly a person comes up to us and introduces himself to Christine, Truke and Bente. This is the guide who will take them to the Airport for their flight to Taiwan. For me to get to the hotel I need Chinese characters to show my destination to the cab driver. The guide writes down the characters of my destination: The Broadway Mansions on Suzhou creek in Shanghai. Christine swirls around and says to me: “You need to go in that direction”. Then we need to say goodbye; we hug and embrace each other.

An icy cold wind sweeps through the big station hall, I fasten the buttons of my jacket and wrap a cardigan around my neck. In the distance, I see the guide striding in front of the ladies. Bente chic and determined, Truke flowing and decisive, Christine clear and bright. I am very pleased to have had such experienced ladies around me; they made me understand China better. The station is still quiet early in the morning on Saturday. Not what I had expected from a megalopolis. At 9:20 a.m. a taxi drives me through the city. The buildings are sky high; highways swing above me. It seems a Rotterdam type of city multiplied by 100 or more. A harbor city next to the sea. Lots of businesses. Restaurants, shady places, traffic. The cab driver is calm and polite. During our trip to the hotel I note in between the high buildings a glimmer of light springing up. It is a reflection of the sunlight on a bleak river. The hotel is located next to this Huangpu River, at the point where it meets the Suzhou Creek which is bridged by the old iron Waibaidu (Garden) Bridge.

With its unique design, this bridge is one of the symbols of Shanghai. A century ago, it was leading (south of the bridge) to lush gardens with flowers.

The hotel, north of the bridge, is a solid, mustard brownish beige stone building. Across the Huangpu River a huge new financial center was built.

The hotel was completed as an exclusive hotel in 1935 by a Shanghai building company owned by Victor Sassoon. From the windows on the front of the hotel one should have a good view on the curve of the Huangpu river.

In 1935, the building stuck out far above all other buildings.

During World War II it was occupied by the Japanese; before that the Japanese community lived already in the Japanese neighborhood (Hongkou district) behind this building. The invading Japanese continued to trade opium from the fifth floor of this Broadway Mansions hotel building after kicking out the Europeans and Americans who were also involved in that trade.

There is a famous picture of this Broadway Mansions hotel, taken when the building work was just completed: it shows the Garden

bridge and part of the Bund in October 1937. The black and white picture is taken from a high floor: it shows that the Waibadu bridge and the Bund are crowded with people - most of them refugees who, chased by the Japanese invading Shanghai, had fled to the International Concession. During the 19th century, external powers pressured China continuously; the weakened and old-fashioned Qing empire with its antiquated institutions was incapable to safe-guard China against foreign encroachment. Foreign powers struck profitable deals in the treaty ports in Chinese cities with dire consequences for China. (For more information read Frances Wood’s “No dogs and not many Chinese” – see also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Century_of_humiliation

).

Nothing commemorates these events when one walks into the reception hall of the hotel. The lobby is sumptuous and richly decorated. At the reception the receptionist tells me my room is not yet available. He acts in a very polished and smooth manner. He directs me to the lobby to wait for my room. A lady with an overbearing chic English voice hangs leisurely in her lobby chair. She chats to friends on the phone. “Am in the Broadway Mansions. Going out tonight with friends….” Through the window the Waibadu bridge is visible. I also see the old English consulate near the Suzhou Creek. I decide to go outside and take a closer look.

I cross the Waibadu Garden bridge towards the Bund. In the old days the trade hub was where I walk, on this side of the river, at the Bund. For two centuries boatmen off loaded their goods at the docks on the Bund, at this curve of the Huangpu river: tea, opium, herbs, weapons.

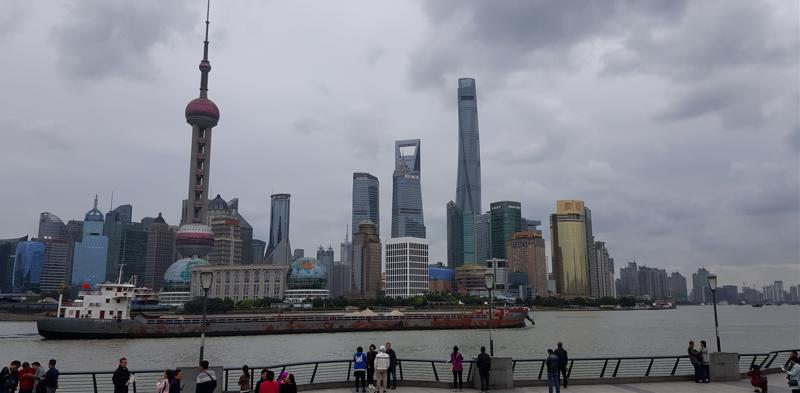

At the other side of the Huangpu river the Pudong financial center points its buildings upwards into the dusty skies. The financial center towers (together with the towers of Hong Kong) are a symbol of modern business in China. Google owns several floors in one of these Pudong towers. Communication world wide, speed of knowledge and speed of manipulation are the new opium but nw everyone is addicted.

From the old now modernized docks on the Bund boulevard the public sees the boats passing by. A stark wind blows in our faces. Stately junks, fishing boats, liners, tourist boats appear and disappear. I hear soft roaring engines, loud squeaking engines, water gurgling.

I continue my path walking towards the South along the Bund. On my right side on the boulevard I see the stately old buildings from the start of the 20th century. Old solid neoclassical style. Bank buildings appeared as well: HSBC, Banque de l’Indochine. To my left, on the

other side of the river: more of those more recent high rise buildings with neon lights, representing the “new, modern” 21st century business powers.

In his book “Half a century in China” by Arthur Evans Moule describes Shanghai as a metropole becoming ever bigger already at the beginning of the 20th century. Moule was an arch-deacon in China. He lived off and on in Chinafor 50 years since 1861. He witnessed the anti-missionary and Boxer rebellions. He organized communities in China to oppose the opium trade.

In his book he describes Shanghai around the year 1890: “The upper waters of the Huangp’u River, near the city of Sungkiang, notorious in Gordon’s campaigns (Gordon brought down the Taiping rebels), widen out into creeks and lagoons, which suggest the existence in ancient days of broader expanses of water covering the whole area. Shanghai itself with its old city walls encircling three hundred thousand people, and its suburbs and settlements containing at least seven hundred thousand more, and nearly twenty thousand people of foreign nationalities; Shanghai with its long line of palaces on the Bund, clubs and banks and hotels and offices; with its countless ramifications of streets and squares with well-paved and well-drained

roads; with its gardens and its wide recreation grounds, its racecourse, its Rotten Row, its theaters, its electric tramways and railways; with all its vigorous commercial life and the enterprises and expansions of trade; with its intellectual culture and educational development, its love of music and of the fine arts; its laughter and its tears; its storm in typhoon and its calm blazing heat; its lives and deaths; its meetings and its partings – Shanghai is afloat all the time.”

I walk back over the Waibadu Garden bridge in the direction of the hotel. A bride and bridegroom have their pictures taken standing against the iron railings of the bridge. The wedding photographer stands with two sneakers on the long veil of the bride’s dress while showing her the pictures just taken. Another young woman in a splendid red dress is leaning against the bridge, waiting for the photographer to capture her beauty as well.

In the Broadway Mansions hotel the receptionist now kindly gives me the access card to my room. It is a wonderful place at the 4th floor. But as soon as I drop my bags a loud banging fills the room. Construction machines for more Shanghai high-rise are roaring under my window at the back of the hotel. So I request to change rooms.

My new room is on the fifth floor: the old Opium trade floor. The receptionist guides me through the long corridor. There used to be offices and apartments here. We pass through a crowd at a marriage

party in the hotel corridor. The old opium trade floor is now a place for celebration. The entrance to my room is obstructed by the party crowd. A big red heart is pasted on the door. The party people look smartly dressed. In suits brightly colored silk dresses - all smiling. The bride and bridegroom are receiving their guests in a room neighboring mine. I make several bows to congratulate them and the guests. I stay for a while just to dip in to this genuine happiness with the guests. My room quickly becomes an extension of their party space: guests get into the room for a cup of tea or to escape the congestion in the corridor. I keep my door open for a while. My clothing needs a change urgently to fit into this party. But when I look through the room window I see how against the backdrop of the modern Pudong financial center boats keep flowing through the curve of the Huangpu Jiang River.

This 113 km long side river of the Yangtse river runs through the city center of Shanghai. This view I’ll remember, as it is so full of history and mischief. I decide then to go visit the city and the Museum.

At the bar near the lobby, dumplings are served – great taste! – I then walk into the city. I walk on the Bund into the direction of the Shanghai Art Museum. The smog is terrible and bugs the throat. I

pass the Peace hotel, which is so famous for its colonial times. Guests have visited it since a long time in this hotel: pianos playing, butlers running; ruined businesses or huge profits – all of that. The interior has an old Habsburg-like sumptuous style with marble and golden decorations. I leave it behind but end up in a fancy Western looking department store. Even with a city map I lose my way to the Museum as, because of all the high rise buildings, it is difficult to find the right direction. So now the cab drives me to the Museum in five minutes. On the street I take a proud selfie, but discover nothing behind the doors – I am in the wrong place! After a ten minutes’ walk I finally arrive at the real Shanghai museum. My expectations are high as Hans van de Kamp, while we were on the 2010 Taiwan and Japan trip with some VVAK members, kept reminding its beautiful collection to me.

The guards start clapping their hands impatiently for me: I am the last person on the floor and run like mad to a window behind which some celadons are smiling at me. Quickly I take many more pictures. One guard starts to run after me – we are five minutes before closing time. But this guard is defeinitely out to get me and me out of his department.

I am the last one taking the stairs down to the entrance hall where I find the exit. I turn around and snap a picture of the marvelous museum building: what a miraculous, lovely and organized museum this is! Then, brutal reality steps in: the smog in the streets. In the park I see many cats. Who takes care of them? – who wants to keep a cat in a closed off apartment, at a high floor in an apartment building?

It is still ice cold outside. The cats follow me through the Park on People’s square. The British Museum in London had some cats relaxing in the exhibition rooms at night, they were looked after by the guards. These cats went back to the streets during the day. Is the same done here?

The traffic is terrible around the People’s Square. It is crowded in this city – one feels that the river is the only escape for the people living in Shanghai. But what treasures I have seen today in the museum! I wish I could tell my friends of the group.

I find myself a jacket as I am getting more and more ill in the cold weather. In a below ground-level shopping mall area I find a black bomber jacket in a boutique. It looks like a gift from heaven to protect me against the ice cold weather. I am energized by owning it and putting it on.

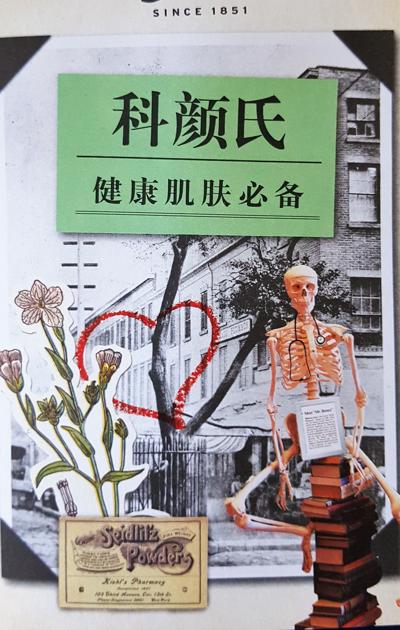

Dusk is falling in the city and the pink and pale NEON lights light up. The Western Brands shops and shopping malls are all around me. I receive a Halloween bag of goodies from a sales representative in a perfume store. In the small bag all the items with skin cream are wrapped five times in thick plastic. The paper sachet in which they are put has an image of a skeleton sitting on a pile of books - the sales department shows their talent: left with bones only, continue reading books.

Via a basement I continue through the Jewelry department – filled with stones, silver, gold and platinum. Everywhere options are given to the consumer to reach for their credit cards.

Via Middle Xizang road and East Nanjing road I continue my way back to the Bund. The neon lit towers of the financial center guide me towards the Bund as their light is visible when walking on one of the main roads towards the river. The towers shine out with their neon lights, the night is setting. I feel alone walking through the streets as the city is packed with merchants, business buildings, ships and art – it has become a universe unto itself. Papers on the road side talk of greed and demolition. A tourist grabs my arm to show me a diamond worth millions in a shopping window. My admiration wears out quickly. What a difference, I think, is this megalopolis with the French village Pieter and I often go to during the holidays: a location in the hills in the Grand Est where one finds healthy meadows, fat cows, hares, vegetable gardens, fresh air and not many people. When dusk comes dogs bark, birds sing, a Renault parks on the parking lot in front of the kitchen door of an ancient farmhouse. The church bell sounds. Venus is visible in the West.

Over the Waibadu bridge I reach my hotel. The Bund is very crowded, ships go by over the Huangpu river. I wish they carry lots of fresh vegetables for all these people.

In the elevator of the hotel I meet a Chinese group of men who are

going for dinner: so I am invited too. They have closed some business deal, I do not know. The food is great, but my throat does not co-operate. It is not just our mutual language exchange, I am still ill and alcohol scares me: so I bow several times a deep bow for the group, with lots of respect for the kindness of the invitation, but have to leave the lively party at the table behind.

From my room I see the financial towers against the black night sky. The neon pink and yellow dog bone forms of the towers throw light on the shaking river surface. The tea I make tastes good; I write down my notes on the trip of several days ago – I feel sad without our group: Truke sends an sms message from Taiwan. Bente and she have arrived ok and are settled in well in the Hotel in Taipei. I call Pieter again, I call Wilma, I hear Rene in the background. We are happy to hear each other’s voices over such a long distance.

I stand on my head in the corridor reflecting on tomorrow… I find it a bit scary a little to go to Suzhou on my own tomorrow… I’d better do some planning.

The night is long, I read a book; I find a catalogue in my bag on Dehua porcelain; admire in it Fujian ware; watch CCTV; think of the Opium traders who settled in this building and their victims. The boats outside have become faint shadows on the river now that the financial towers have shut down their neon lights. Moule wrote in his book about Shanghai: “I cannot exclude Shanghai from the narratives of my recollection of China during the past fifty years. It was the first inhabited place which I saw on my arrival. It will be the last to fade from sight when I leave China.” Shanghai night life travels through my imagination when I turn off the lamp next to the bed. 140 years after Arthur Moule’s travel blog Shanghai is still afloat all the time.

Hereby the information from the Shanghai Museum:

In this museum many visitors seem to have caught a cold: there is a chorus of sneezes and coughs echoing from all higher floors in the wide space of the central entrance hall. Floor to ceiling this museum houses costumes, jewelry, jades, porcelains, coins, woodcarvings, furnitures. I follow the advice of an Englishman and attend the exquisite exposition of early Buddha statues. In this department the visitor finds Buddha statues from the Wei, the Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties.

"In the beginning of the first century A.D. Buddhism came from India and Central Asia to China. The work of Buddhist missionaries relied not only on scriptures but also on images. Buddhism was sometimes called “the religion of images”. The earliest known Buddhist images with dated inscriptions are gilt bronze figures from the fourth century A.D. During the Northern Wei period A.D. 386 – 535). Buddhist sculpture was under heavy influence from Ghandara (northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan). Figures of the Buddha form this period typically have deep set eyes, strongly Western facial features, and stocky bodies. Towards the end of the Northern Wei period however, these influences were assimilated and softened, and solid bodies gave way to elegantly flowing robes and girdles. When Northern Wei was succeeded by Eastern Wei (A.D. 534 – 550) and Western Wei (A.D. 535 – 557), styles in the western part of north China diverged slightly from those in the eastern part. In the eastern part, the

Northern Wei’s style continued. Buddhist figures of Eastern Wei have close fitting robes with the lines of pleats clearly and simply expressed. Those of the Western Wei have robust bodies, faces that are round and full, and intricically pleated robes. Under the subsequent Northern Qi dynasty (550 – 577 A.D.) statues became slim and graceful, with delicate garments and sharp linear details. Northern Qi figures are notable for their wonderfully serene facial expressions. A characteristic which persisted into the Sui dynasty (A.D. 581 – 618)."

Pictures, left to right per row, start at the top:

1. A section of Buddhist Pagoda, stone - Northern Wei, 386 - 534 A.D.

2. Lion - ???

3. Bodhisattva, gold painted - Jin, 1115 - 1234 A.D.

4. Three amitabha Buddha's, bronze, Sui 518 - 681 A.D.

5. Buddha stone - Tang, erected by Han Bian - Zhi, Tang 661 A.D.

6. Buddhist stele - Northern Qi, 550 - 577 A.D.

7. Buddha stone - Eastern Wei, 534 - 550 A.D.

8. Figure playing Lute, pottery- Eastern Han, - 25 - 220 A.D.

9. Two figures, bronze - Warring states, 475 - 221 B.C.

10. Three Figures, painted wood, Warring states, 475 - 221 B.C.

11. Lokapala, (guardian) stone - Song, 900 - 1279 A.D.

12. Buddhist stele with figurines and inscriptions on four sides, stone - The first year of Wuding. Eastern Wei, 543 A.D.

The porcelain department of the Shanghai Museum

The stairs take me to the porcelain department on a higher floor. A yellow dish with Sancai design from the Tongzhi reign (1862 -1874 AD) is the first I see. It is indeed a dream to be here. Hans Swaan of the VVAK shared his studies with me on yellow glaze types. He shared information with me on an email exchange with the famous Nigel Wood on antimon yellow in porcelain. I am so lucky having had so many teachers around me.

I phone Pieter. He is doing fine, but says I sound very ill – he is right, of course: I do have a cold and am coughing too much- and… that I should go back to the hotel. But, with all this art around me, how could I? So, by way of exception, I do not follow his advice, and continue my tour.

I decide to start at the ceramics department with the celadons (green glazed stone wares). An Huizi celadon chamber pot of the Western Jin is the first to catch my eye. The animal radiates an air of power.

As this is such a big collection and there is so much to know about

porcelain, in the following pages are listed the informations pasted on the wall of the Shanghai museum. Photographs of the Shanghai collection accompany the numbered texts:

1. Mature celadon was achieved in the first century A.D. (Eastern Han Dynasty). Scientific tests show that the first century celadon wares and black glazed wares from Shanyi and Zhejiang province have technical qualities that meet the modern definition of porcelain. In the third and fourth century improvements in the luster of the glaze are seen in wares from Yuezhen, Wuzhou and Ouyao. The wares were richly decorated with much use of modelling, applique, openwork, coloring and incising.

Pictures:

1. celadon Huzi chamber pot - Western Jin A.D. 265 - 317

2. brown-glazed quin bodied jar with modeled animals - Eastern Han A.D. 25 - 220

3. celadon chicken-headed ewer - Western Jin A.D. 265 - 317

4. celadon lion-shaped Bixie (evil spirit exorcises) - Western Jin A.D. 265 - 317

5. celadon jar with modeled human figurines, birds and architecture - Western Jin A.D. 265 - 317

6. green ware jar with human figurines and buildings - Western Jin A.D. 265 - 317

7. celadon ram with brown spots - Eastern Jin A.D. 317 - 420

8. celadon jar with modeled human figurines - Wu state of three Kingdoms A.D. 222 - 280

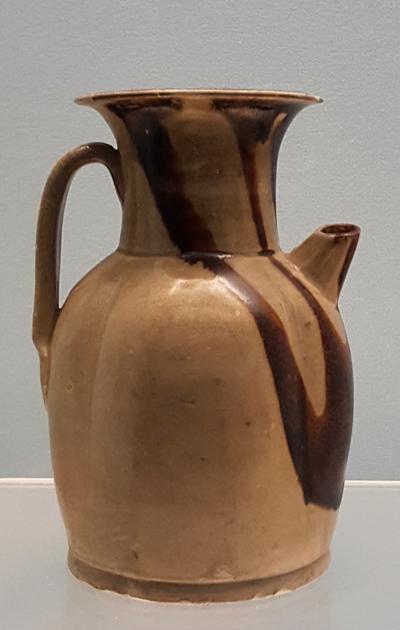

2. The polychrome glazed pottery of the Tang dynasty represents a dramatic advance in ceramic production. The porcelain industry also underwent a rapid development in this period and the succeeding Five Dynasties period, a development spurred by competition between north and south. The Yue ware of the south and the Xing ware of the north were the highest achievements of the two regions.

Picture:

1. polychrome glazed pottery jar, Tang A.D. 618 - 907

3 The polychrome glazed pottery of the Tang dynasties - called Tang-sancai - is made of white clay coated with a layer of glaze and fired at a temperature of 800 C. Lead oxide served to flux the glaze; the coloring agents were copper, iron, manganese and cobalt. The most familiar examples of Tang Dynasty sancai pottery are animated figurines of people and animals. Such types of figurines and plates are on show in the museum. In the Tang dynasty the production of Yue ware celadon was concentrated in the Zhejiang province

centering on “Gongyao” kiln at Shanglinhu in Cixi and neighboring kilns at Yinxian and Shaoxing. These kilns produced not only yellowish-green celadons, but also the remarkable blue-green mise (secret-color) celadons. The production of Yue ware peaked in the Five Dynasties and early Song period, then slowly declined under competition from kilns in the Longquan (in the South Eastern Zheijang province) area.

Pictures:

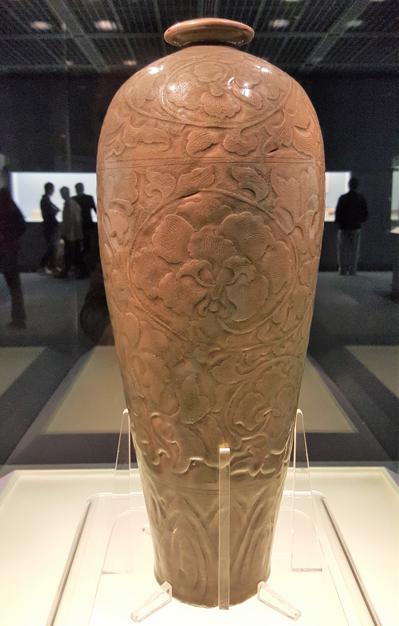

1. celadon jar with carved and incised peonies design, Yue ware - Northern Song A.D. 960 - 1127

2. white glazed pottery figurines of women (dancing, playing Xiao, playing Pipa), Sui A.D. 581 - 618

3. celadon water jarlet with four feet, Yue ware - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

4. celadon jar with four rings and carved lotus petal design, Northern Qi A.D. 550 - 577

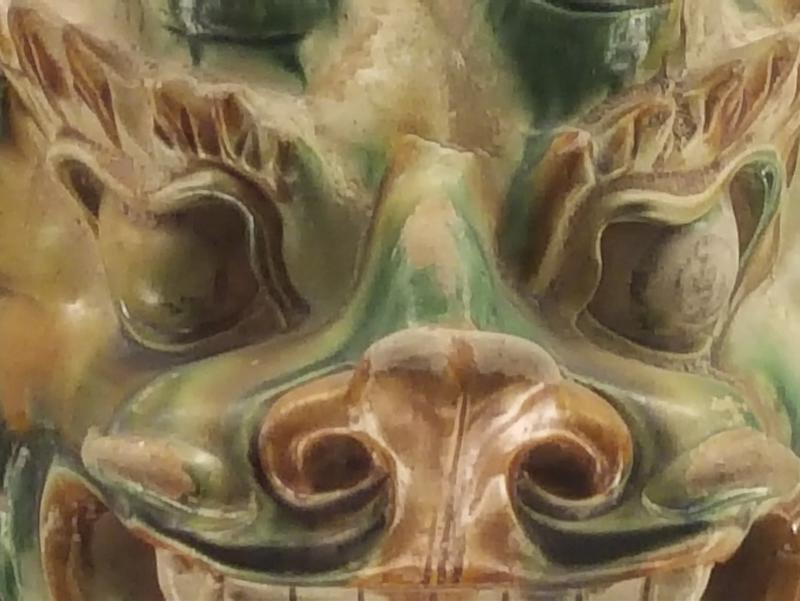

5. polychrome glazed pottery statue of heavenly guardian - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

6. face of a statue of a Tomb's guardian beast of polychrome pottery - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

7. celadon pillow with brown and green floral design - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

8. celadon pot with brown decoration, changsha ware - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

9. polychrome glazed pottery statue of a man on a camel - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

4. White porcelain was first made in the early third century, as shown by examples from the Eastern Han tombs of Changsha in the Hunan province. Over the next 700 years it was produced in increasing

quantity in North China and its quality improved. The most outstanding types, produced at kilns at Neiqiu and Lincheng in Hebei province, was Xing ware, which Tang connoisseurs praise by likening it to silver or snow. Changsha ware was made by kilns as Tongguan town in the suburbs of Changsha in Hunan province (also known as Tangguan ware). It is known for imaginative shapes and rich decorations often including underglaze brown and green spots produced by iron and copper. The Tongquan kilns were famous for producing a red color as well: laying the foundation for later underglaze red porcelain. Changsha wares are shown here from the Tang.

5. Northern variegated-glazed porcelain of the Tang period, called “huayou” has a glaze which sets splashes of sky-blue or moon-white on a black-yellowish brown or yellow ground. The sharp contrast has

a vivid and spontaneous effect. The best and most famous examples were made at Lushan and Jiaxian in Henan province. Simple wares came from Juxiang and Neixiang in Henan province.

Pictures of Huayou ware, left to right:

1. blackglazed jar with colourful spot - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

2. polychrome glazed pitcher - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

6. Marbled pottery, called “jiaotai”, was an invention of the Tang period. To make this ware a sandwich of alternating layers of white and brown clay was made (sometimes more than 2 colors were used). Thin slices were then cut from the sandwich and applied to the surface of a pot, alternatively it was then glazed and fired. Many different marbling patterns were possible in this technique, one of the most popular resembles woodgrain.

Pictures of marbled pottery:

1. colour twisted pottery pillow with inscription “Du Jia Hua Zhen” - Five Dynasties/ Northern Song A.D. 907 - 112

2. colour twisted pottery pillow - Tang A.D. 618 - 907

Am so impressed with this collection. I continue to the Song, Liao, Jin and Yuan dynasties porcelains (960 – 1368 AD). In this period of more than 300 years from the late tenth century to the mid fourteenth century the ceramic industry flourished spectacularly.

7. During the Song Dynasty the Ru, Guan, Ge, Ding and Jun kilns manufactured the five famous porcelain wares for the imperial court, at the same time folk kilns in both the south and north produced many distinctive wares of high quality. Porcelain manufacture in the north under Liao and Xixia rule from the tenth to twelfth century brought influences of ethnic minorities into the ceramic industry. There are on

show all sorts of beautiful pots; mei ping vases; there is also Ge ware with the so typical millet glaze. In this time greyish-green glazes with crackles occur. A glaze with large black crackles, a glaze with large black crackles and small yellow crackles also occurs, this is called jinsitiexian (“gold thread and iron wire”).

There is Ru ware on show. Lots of Chinese admiring it with me.

Pictures:

1. washer, Ru ware - Northern Song A.D. 960 - 1127

2. vase, Jiaotanxia Guan ware - Southern Song A.D. 1127 - 1279

3. rose-red glazed drum shaped washer, Jun ware - Northern Song A.D. 960 - 1127

4. five-footed washer, Ge ware - Southern Song A.D. 1127 - 1279

5. moon-wgite glazed meiping vase, Jun ware - Jin A.D. 1115 - 1234

6. moon-white glazed jar with lotus-leaf-shaped lid, Jin - early Yuan, A.D. 1115 - 1300

7. washers, Ru ware - ??

8. Ru ware is first on the list of the five famous Song porcelains, it was made in the late Northern Song period. In 1968 the Shanghai

museum found kiln furniture and fragments of Ru ware at Baofeng0 in Henan province, so the Ru kilns were confirmed Baofeng. Kiln sites remain undiscovered for Northern Song Guan ware and extant Ge ware. For the Southern Song Guan ware there have been important discoveries however. After Jiaotanxia kiln (official) was found at the foot of the Mount Wugui in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, The Xiuneisi official kiln was also found a the Laochudong in Hangzhou in the 1990’s. Several excavations were done by Archaeologists on both sites.

Here on show are great objects from both types of kilns: a Ru ware washer and Jiaotanxia Guan ware vase and bowl.

9. Yaozhou ware kilns in the Tongchuan county, Shaanxi province, began producing celadon, black porcelain and pottery with coloured glaze in the Tang period. The celadons made by the Yaozhou kilns in the five Dynasties are the best ever made in Northern China. Yaozou is also famous for ware with a yellowish green glaze and smoothly carved or moulded designs. These were made in the Northern Song and Jin periods. Some wares were requisitioned for the imperial court. Yaozhou wares were so popular during the Song period, that

they were widely copied: notably at Xicun in Guangdong province and at Yongfu and Rongxian in the Guangxi autonomous region, and by kilns at many places in Henan province.

Pictures:

1. tri-footed celadon vase with carved interlaced flower design, Yaozhou ware - Northern Song A.D. 960 -1127

2. moon-white glazed covered jar, Yaozhou ware - Jin A.D. 1115 - 1234

3. celadon foliated bowl, Yaozhou ware - Five Dynasties, A.D. 907 - 960

4. celadon vase with carved floral design, Yaozhou ware - Song A.D. 960 - 1127

5. celadon stem disch in the shape of men carrying a lotus leaf , Yaozhou - Northern Song A.D. 960 - 1127

I miss sharing all this knowledge and beauty with the group. We travelled together for the last 2 weeks. The big city and big crowd dynamics make me feel lonely. The visitors of the museum swim around me to view the big stream of attractive objects. The glimmer on the Huangpu river at dusk is like the moon-white glazes on the , jars here.

The abnormal amounts of great Chinese art and folk art admired during the last 2 weeks have given me the opportunity to understand a wide range of porcelain recipes and crafts and kilns.

Good the VVAK had a lecture by Stacey Pierson on colours in enamels at the Society last year. Her lecture made us ingest the

importance of pigments. Check out her book: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Chinese-Ceramics-Stacey-Pierson/dp/1851775765 ) . The pigments available per area have decidedly played a major role in the type of ware produced in an area. It is the combination of ingredients and master chefs in porcelain work shops which is critical to this art. Perhaps with bad paint one can make a painting still look good for a small time, but in a kiln all bad materials attract directly the eye’s attention. Good I already have a catalogue on the Shanghai Museum by Kong Lihang and Zhang Ping, cause no English books can be found here. Black porcelains are on show too.

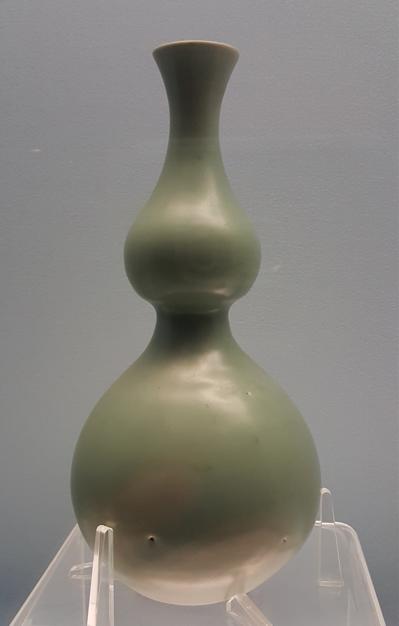

Pictures:

1. celadon gourd-shaped vase, Lonquan ware - Yuan A.D. 1271 - 1368

2. celadon dish with applied cloud and phoenix design on exposed body, Longquan ware - Yuan A.D. 1271 - 1368

3. black-glazed bowl with yellowish slip, Jizhou - Southern Song A.D. 1127 - 1279

4. celadon Bo (bowl) with modeled dragon design, Longquan ware - Yuan A.D. 1271 - 1368

5. white glazed covered jar with carved plum spray design, Jizhou ware - Southern Song - Yuan A.D. 1127 - 1368

10. In the four centuries from Song through Yuan, both north and south produced new varieties of black porcelain. The black-glazed “hare’s fur” tea bowls made by the Jian kiln in Fujian province, with a pattern of radial streaks in the glossy black glaze were especially favoured for the tea-drinking games. In the West they are sometimes known by their Japanese names temmoku. Black glazed wares from the Northern kilns in Henan, Hebei and Shaanxi have spotted rather than streaked glaze and are called “oil-spot” or “oil-drop” wares. The hare’s fur and oil-drop glazes are similar in process of formation,

owing their patterning to iron crystals that form within the glaze as it cools.

Pictures:

1. black-glazed vase with Xixia characters, Lingwu ware - Xixia A.D. 1032 - 1227

2. bowl with paper-cut phoenix design, Jizhou ware - Song A.D. 960 - 1279

3. black oil-drop glazed bowl, Huairen ware - Jin A.D. 1115 - 1234

I walk over to the Cizhou wares.

11. Cizhou wares from the vicinity of Handan in Hebei province. This is famous folk porcelain of the eleventh and twelfth century (during the Northern Song and Jin Dynasties). Cizhou ware

decoration was executed by painting, incising, carving and sgrafitto. It is particularly celebrated for underglaze black or brown painting on a a white ground and for incised and sgrafitto designs. The design often incorporates popular subjects executed in the fresh and lively style of folk art. Then I note the impact of the Yuan here as well: The Yuan chased the Song towards the South East area of China. These Southern Song produced porcelains while the pressure put by the Yuan on the borders of the Southern Song dynasty was palpable. Slowly but sometimes extremely fast the Yuan took over the Song territory. The Southern Song still ruled from 1129 AD for about another 150 years. Finally after two decades of sporadic warfare, Kublai Khan's armies conquered the Song dynasty in 1279. The Mongol invasion led to a reunification of areas under the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 AD).

Pictures:

1. Child-shaped pillow with black designs on a white ground, Cizhou ware - Jin Dynasty, A.D. 1115 - 1234

2. Pillow with black lotus bouquet, design on white ground, Cizhou ware - Northern Song, A.D. 980 - 1127

3. Polychrome glazed pottery pillow with incised bird and flower design, Cizhou ware - Jin - Yuan Dynasty, A.D. 1115 - 1368

4. White glazed bowl, with incised interlaced spray designs, Cizhou ware - Northern Song, A.D. 960 -1127 (donated by Chen Qisheng)

5. vase with black design of flowers on a white ground, Pacun ware - Northern Song, A.D. 960 - 1127

6. Vase with black painted and incised cloud and wild goose design on white ground, Cizhou ware - Yuan A.D. 1271 - 1368

7. Covered jar with brown leaf design on white ground, Jizhou ware - Yuan, A.D. 1127 - 1368

8. Dish-mouthed pot with carved rings, dish with moulded design, phoenix head ewer with applique decoration, yellow glazed pottery pot, Polychrome glazed pottery - Liao, A.D. 947 - 1125

12. Jingdezhen in Jianxi province, known during the Song for its bluish-white Qingbai porcelain (refer to: the visit to Jinkeng on

Monday October 24), rapidly came to dominate porcelain production after it began mass-producing underglaze blue in the Yuan period. Official kilns dedicated to the production of imperial wares were established at Jingdezhen in the early Ming periods. These imperial kilns introduced a large number of fine wares. In the Qing period many more new wares were created by this imperial kiln, which drew on the long experience of both folk and imperial kilns. By that time Jingdezhen was famous for porcelain throughout the world. There is a wonderful Qingbai bluish-white glazed buddha statue on show (see picture).

Jingdezhen ware of the Yuan 1271-1368 AD looks wonderful. It has a grey-greenish colour and a drapery in Orange/reddish brown. It’s hand is half-open and holds a (?).

13. Jingdezhen qingbai porcelain of the Song and Yuan period has a thin, evenly made, translucent body and a jade-like, pale bluish-white glaze. Its refined decoration, made by carving, incising or moulding shows a fluent craftsmanship and careful composition. During the Yuan period Jingdezhen produced a porcelain called “shufu” after the two characters inscribed on some pieces. This inscription may mean that the pieces were ordered for the “Shuniyuan”, the ministry of

defence. The glaze of it is thick and somewhat opaque, white with a faint blue-green tint. There is another bluish-white glazed saucer, Jingdezhen ware from the Yuan, in the form of a flower.

Images:

1. Qingbai bluish/white glazed bowl with carved peony design, Jingdezhen ware, Southern Sung A.D. 1127 - 1279

14. In the mid and late Yuan, so during the fourteenth century, the Jingdezhen kilns began to produce porcelain of high quality, decorated in underglaze blue – familiarly called “blue-and-white” in the West. It was made by painting cobalt oxide under a nearly colourless glaze, similar to Qingbai glaze. The first designs were densely painted in an intense shade of blue.

Images:

1. Qingbai (Bluish White) glazed Buddha statue, Jingdezhen ware - Yuan A.D. 1271 - 1368

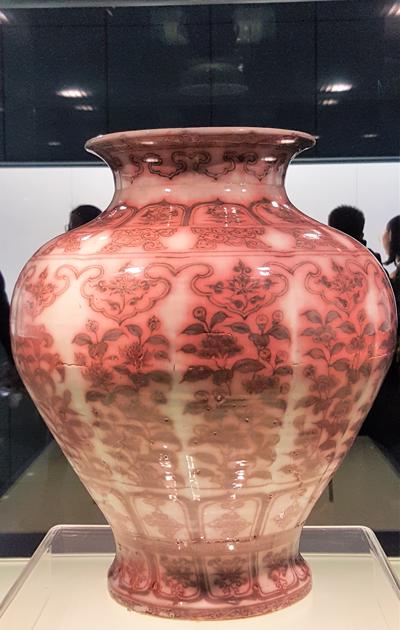

2. Vase with reserved underglaze red design of figures, Jingdezhen ware - Hongwu reign A.D. 1368 - 1398, Ming

3. Dish with white fish with algae design on blue ground, Jingdezhen ware - Xuande reign A.D. 1426 - 1435, Ming

4. Foliated dish with underglaze blue design of melons, bamboo and grapes, Jingdezhen ware - Yuan A.D. 1271 - 1368

5. Vase with underglaze blue design of interlaced peonies, Jingdezhen ware - Yuan A.D. 1271 - 1368

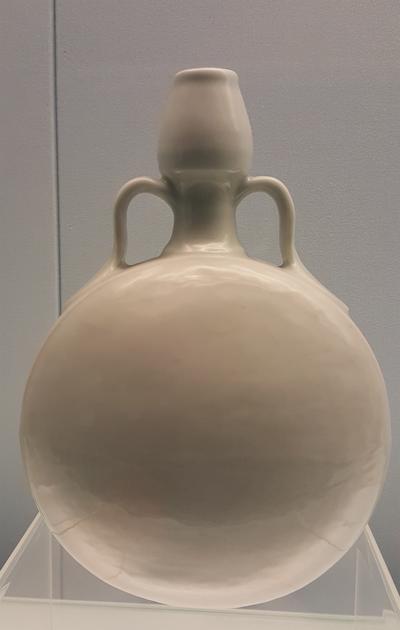

6. Oblated pot with underglaze blue design of camellia sprays, Jingdezhen ware - Yongle reign A.D. 1403 -1424, Ming

7. Foliated dish with underglaze red design of flowers, Jingdezhen ware - Hongwu reign A.D. 1368 - 1398, Ming

8. Melon-shaped jar with underglaze red design of season flowers, Jingdezhen ware - Hongwu reign A.D. 1368 - 1398, Ming

9. Same melon-shaped jar (see point 8)

15. Early underglaze blue porcelains have been found in large quantities in the Islamic world and they are depicted in Islamic miniature paintings suggesting that the production of underglaze blue was to a large extend stimulated by demand from the countries of the Islamic world. All examples are shown

here in the museum: a beautiful blue-and-white stem cup, a plate and the famous blue-and-white glaze.

The Hongwu vase with underglaze red and the plate with red-brown flowers from Jingdezhen shown here in the museum are examples for the transition to colourful polychrome porcelain. Objects on show seem the proof-of-concept for underglaze red porcelain objects. As well is shown a beautiful flask blue-and-white Xuande Jingdezehen with underglaze blue reclining. There is a bean-green saucer with a Xuande mark in blue in the inside and a stem bowl with underglaze red fish. All the Ming Xuande reign objects have wonderful colours, ox red glazed mid blue. Also a “falancai” red and green vase of the early fifteenth century is on show. (Please refer to the pictures in this chapter).

16. Folk and imperial porcelain kilns of the mid-fifteenth century – meaning: the Zhengtong (1435 -1449 AD), Jingtai (1449–1457 AD) and Tianshun (1457 - 1464 AD) reigns - bear reign marks. As a result these decades have sometimes been considered “a dark age” in Jingdezhen history. But a great many Ming porcelains excavated by archaeologists or handed down objects should be assigned to this

time. The wares are underglaze blue, underglaze blue with overglaze red, doucai (design outlined in underglaze blue and filled in with overglaze colours; contrasting colours like red and green) and monochromes in white and green. The main product was underglaze blue and many pieces are of superb workmanship. The Doucai wares from the Chenghua (1447 – 1487 AD) period contrast with the crackled glaze Ge ware bowl on show. What a contrast between the colourful decorations on porcelain and the purist style of Ge ware.

Then there is also the beautiful egg yolk yellow and green plate made during the Zhengde (1505–1521 AD) reign in the Ming period in Jingdezhen: a green dragon swings his awesomely long body in the heart of the plate. I continue to Hongzhi and Jiajing wares of Jingdezhen.

17. During the Jiajing reign (1522-1566 AD) the Jiajing reign official kiln quality declined but the porcelain production quantity rose. The

Jiajing underglaze blue has a strong purplish cast owed to the use of “Mohammedan” cobalt. Wucai (five enamels or "five color ware". Note it often refers to mostly three enamels (red, green and yellow) within outlines of blackish dry cobalt, underglaze blue, plus the white of the porcelain body; in Europe named “famille verte”) and doucai (design outlined in underglaze blue and filled in with overglaze colours; contrasting colours like red and green) wares are brightly coloured red-glazed and green-glazed porcelains with designs painted in gold), which make their appearance in this period. The production of monochrome wares decreased significantly. The output as a whole is characterized by an unusually wide variety of shapes and unusually large objects. Among porcelains handed down to the present day the brief Longqing reign (1567 -1572 AD) is represented chiefly by underglaze blue and wucai objects in the style of the preceding Jiajing period.

A wonderful blue glazed bowl with carved dragon design is from Jingdezhen. It is from the Jiajing reign. A square box with a lid in underglaze blue and dragon medallions from the Longqing reign (1567 – 1572 AD) looks to me somewhat like a box in the VVAK collection. I continue to the Wanli era porcelain:

Images:

1. Watering pot with underglaze blue design of interlaced lotus flowers, Jingdezhen ware - Xuande reign A.D. 1426 - 1435, Ming

2. Vase with reserved underglaze red design of figures, Jingdezhen ware - Hongwu reign A.D. 1368 - 1398, Ming

3. White glazed oblated pot with two ears and veiled design Jingdezhen ware - Xuande reign A.D. 1426 - 1435, Ming

4. Vase with green and red design of interlaced Lotus flowers, Jingdezhen ware - early 15th century

5. Red glazed dish, Jingdezhen ware, Xuande reign A.D. 1426 - 1435, Ming

6. Doucai (contrasting-coloured) dish, Jingdezhen ware, Chenghua reign A.D. 1465 - 1487, Ming unearthed from Zushan, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province

18. During the Wanli reign (1573 – 1619 AD) the Government invested heavily in manpower and materials to produce porcelain for the imperial court. The wares were mostly conventional with few new inventions added. Folk kilns became more active. The styles began to

change in the Wanli period. Late in the Wanli reign the official kilns for monochrome ceased production. The folk kilns became more active and as a consequence styles began to change.

Production fully developed the below listed styles:

a. Wucai (underglazed blue wucai). Wucai means five enamels or "five color ware". Note it often refers to mostly three enamels (red, green and yellow) within outlines of blackish dry cobalt, underglaze blue, plus the white of the porcelain body. All in all making up five added colors

b. Doucai (opposing colours; design outlined in underglaze blue and filled in with overglaze colours; contrasting colours like red and green) wares are brightly coloured red-glazed and green-glazed porcelains with designs painted in gold) on the white porcelain body

c. Sancai (Chinese name meaning "three glazes" of a low fired lead glaze based style of decorating earthenware pottery regardless of the actual number of colours of the item. If there is a technical explanation of the term it might be that the colours actually are based on specifically three different oxides i.e. iron giving yellow to brown hues, copper giving green or occasionally brown colours and the rare cobalt for blue. The colours can occur as monochromes or together) types rose dramatically. Refer to the text by Nilsson

d. As a result of the above: Monochrome porcelain remained few.

19. In the seventeenth century - from the late Wanli (Ming dynasty) till the early Kangxi (Qing dynasty) reign - the folk kilns at Jingdezhen

developed themselves unprecedently. This was partly because of the decline of the imperial kilns and partly because of sharply increased exports to Europe. Unconstrained by the traditions of the imperial kilns the potters created many new designs for export to other countries. The result of it were thus new styles, signifying the transitional period from late Ming to early Qing.

A blue-and-white censer with auspicious animals of the Chongzhen reign (1622 – 1644 AD – he was the last Ming emperor) is shown. See picture.

Thirty minutes are left for me in the museum - not a lot to admire the Qing porcelain collection! It is visible in this museum that the influence of empires is reflected in the porcelain colours and designs. Porcelain of the transitional period from 1620 - 1683 AD is exhibited. See on the transitional period: Jan-Erik Nilsson’s site: http://gotheborg.com/glossary/transitional.shtml . By 1620 AD the Ming emperor Wanli dies. Chongzhen becomes then the last emperor of the Ming dynasty. During his reign the Ming start to lose control over the land as well as the control over the porcelain factories in Jingdezhen. By 1654 the first Qing reign emperor named Kangxi takes over power. He is a descendant from the Manchu people; as an

emperor he takes care to immerge Chinese (Han) style into the art taste at court (his grandson Qianlong copies Han style art even more relentlessly into porcelain). In 1683 AD Zang Yingxuan is appointed by Kangxi as director of the Jingdezhen imperial factory. Zang Yingxuan is the first of three famous directors of the Jingdezhen imperial factories. The emperor Kangxi reigns for 61 years over China.

The Qing exposition here in the Museum is extensive. All of a sudden I walk into the export porcelain installation of the Museum, of which a part of the collection was donated to the museum by Henk B. Nieuwenhuys. There are estimations that in history about 20 Million pieces of porcelain were imported to Europe by the VOC. August the Strong, king of Poland and elector of Saxony (Dresden, 1694-1733 AD) built an enormous export porcelain collection in Dresden. See for more info on Jan- Erik Nilsson’s site: http://gotheborg.com/glossary/august_the_strong.shtml So Henk B. Nieuwenhuys donated in 2008 97 objects of the best export porcelain to the Shanghai museum. In exchange for his donation to the Museum, he required an exhibition of the Emperor’s porcelain from this Shanghai Museum to be held in the Netherlands. That exposition

was held in the The Hague Gemeente museum. That enormous presence of D.F. Lunsingh-Scheurleer in the VVAK arena. Many VVAK members went to admire the objects in the Gemeente Museum; I visited it on August 14, 2011; bought the catalogue.

20. With the recovery of traditional techniques and the invention of new types of style Jingdezhen porcelain production entered a flourishing new area during the Kangxi reign (1662 – 1722 AD) . The most important products of that period were peachbloom, langyao red (ox-blood or sang-de-boeuf), sky blue and green glazed wares. Overglaze decorations such as wucai and doucai were also much refined (in the West wucai is called during the Qing “famille-verte” ). Falangcai was a new invention of the highest quality. Falangcai is an early term referring to enamel decoration on porcelain. Falang is likely to be a corruption of the word "foreign". Although still a topic of scholarly debate, the term falangcai is usually applied to the particularly fine enameled decorated wares in the imperial workshops of the palace in Beijing using the fully developed famille rose/fencai palette. The application of the enamels on these porcelains is very sophisticated and the pictorial decoration is often accompanied by a calligraphic inscription in black enamel and imitations of seals in pink enamel. In the past such enamels have also been known by the name Guyuexuan (Ancient Moon Studio).

20. During the Qing dynasty all the variations of doucai, falangcai, wucai, fencai and monochromes were produced with a very high quality. Yongzheng (1723-1735 AD) - the son the earlier mentioned Kangxi emperor - has promoted the best falangcai quality of the seventeenth and eighteenth century. And Yongzheng underglaze red is the finest in Chinese ceramic history. Techniques in the imperial kilns advanced rapidly in this period as the Yongzheng emperor was extremely fond of porcelain. The imperial Qing court sent the court official Tang Ying and others to Jingdezhen to oversee production of porcelain. Tang Ying was a friend of the Italian working at the Qianlong court: Giuseppe Castiglione who was both a Jesuit and a court painter during three Qing Dynasties in China, from the reign of Kangxi, through the Yongzheng to the Qianlong period respectively. Tang Ying was the director of the porcelain factories from 1736 – 1753 AD.

21. The Guangcai style ( see here: http://www.eguangzhou.gov.cn/2017-09/06/c_102335.htm ) from Canton I did not find in this Shanghai museum – likely objects decorated in Guangcai style can to found in Guangzhou. The Guangcai ware is typical for its contrasting colors with scarlet, pink and green as its main pigments. Guangcai is a combination word for “porcelains painted in Guangzhou with gold and other colors”. Abundant gilding later set this type of enameled porcelain apart from the famille verte type of porcelain. Guangzhou as a commercial center exported a lot of Guangcai wares.

The Shanghai museum becomes much less crowded; people are leaving. It is 17:00 soon. I enjoy the Yongzheng wares and keep making pictures with my MP 16 smartphone camera: stem bowls, vases and plates. The decorations on the porcelain are incredibly precise.

22. The monochrome porcelains of the Kangxi period include red, yellow, blue, white, green, purple, brown and black. To these the Yongzheng potters added lake-green, tea-dust and robin’s egg glazed wares, along with copies of such famous Song wares as Guan, Ge, Ru and Jun. In 1735 AD the imperial super intendant Tang Ying compiled a list of the wares being produced in the Yongzheng official kilns. His list entitled “Tao Cheng Ji Shi” contains 57 wares: the majority are monochromes, but many imitations of Antique wares from Song and Ming are also listed. The Coral red glazed dish – from Jingdezhen made during the Yongzheng reign - has tiny bubbles. It was donated to the Museum by Mr. Yan Zhongzhen. Then follows a turquoise glazed bowl with archaic bronze design. There is a great Ru-type vase and a red cup with a lid. The Jiangdouhong (literally meaning “cow-pea red”) porcelain is so named for its colour which is obtained by high temperature firing of a copper oxide. It is a much prized monochrome ware introduced by the official kilns of the Kangxi reign. It is one of the finest Qing wares. Depending on the exact shade of red obtained during firing the products were given a variety of names including: “pure red” , “bright red robe”, “beauty’s blush”, “baby’s face” and “peach blossom”. The ware is known as peach bloom porcelain in the West.

Ru-type, tea dust, celadon and peachblossom it is all on show here at the Shanghai museum!

23. The Qianlong reign (1736 – 1795) at Jindezhen brought together all the finest porcelains of the past. Qianlong’s taste and enthusiasm brought together imitations of all the famous old wares and were added to the set of traditional wares that continued in production. Lifelike wares and ornamental porcelain began to be produced in large quantities. From a technical point of view Jingdezhen reached it’s highest level of achievement in the Qianlong reign. It produced porcelains imitating objects in other materials such as gold, silver, stone, lacquer, mother-of-pearl, bamboo, gourd, wood, jade and bronze. Other technical tour-de-force objects include open work and nested objects with freely revolving inner parts. Life-like ceramics are executed in great realistic detail. Jade like porcelains are shown, a twin bodied vase and a quartz bodied vase.

24. After the Jiaqing reign (1796 – 1820 AD) and the Daoguang reign (1821 – 1830 AD), porcelain production at Jingdezhen went into a decline which impacted both the folk and the official kilns. Nevertheless some fine porcelains were produced between the Jiaqing reign and the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911 AD. Some of the Jiaqing and Daoguang fencai (enamel which is both opaque and PbO-K2O powdery – also called Ruancai). If we look at the colour palette of typical fencai wares, we note that the iron-red and probably green are from the wucai palette. The iron-yellow of the wucai is replaced by opaque lead stanate yellow of the falang palette. Fencai acquires the opaque or powdery look due to the presence of a substance called po li bai, an opaque lead-arsenate white enamel. The shading effect ,which gives perspective to a motif, is achieved by altering the ratio of colored enamels to this white enamel. A typical example is that as applied for the pink floral petals. Another distinguishing enamel is the opaque lead stanate yellow which is visually different from the more transparent iron yellow of wucai. Some other falang colors such as blue and pink are important enamels in the fencai palette. Some of the Jaiqing and Daoguang fencai wares rival Yongzheng and Qianglong fencai. Pieces with the mark “Shen de Tang” have been highly regarded.

25. Note: ceramics produced during the Ming and the Qing (1368 – 1911) were produced at different locations. There were many porcelain kilns everywhere in China. Famous Chinese wares include white Dehua ware from Fujian province, Yixing zisha (“purple clay”) stoneware from Jiangsu province, flambé Shiwan ware from Guangdong province and white Zhangzhou ware from Fujian province. In the North of China two important mass-produced wares were Fahua from Shaanxi province and Cizhou from Hebei province.

The information board of the museum explains that “the Dehua kilns are located in a remote mountain area of Fujian province. During the Song and Yuan periods Dehua produced large quantities of Qingbai porcelains for export. In the Ming and Qing periods it was famous for the pure white porcelain known in the West as Blanc-de-Chine. Lifelike figurines with fluid drapery are the best known blanc-de-chine type. Of the period in the Ming the most famous Dehua potter was He Chaozong (link to the dehua travel day…) .

The white glazed statue of avalokitesvara bodhisattva with drapery and the “He Chaozhong” mark – Dehua, Ming – have a flowing style and strong design. In the next area I note six teapots: one is speckled grey, the rest is red-brown – a typical Yixing type color. A white glazed bowl of grey green from around 700 A.D can be found here as well.

26. The centre of production for Yixing zisha pottery is Dingshu town in Yixing county, Jiangsu. In the Ming period several generations of famous zisha potters worked there. In the Qing period Literati collaborated with zishu potters to produce large quantities of finely made tea-pots and decorative items appealing particularly to literati taste. Zisha wares with a Jun type glaze called Yijun ware rivals of the flambe of Shiwan ware from Guandong. During the Ming and Qing periods Shiwan ware from Guangdong, Zhangzhou ware from Fujian and Fahua ware from Shaanxi all developed considerable individuality. The Shiwan kilns were continuously active over a very long period. Much Zhangzhou was handed down for generations and recently pieces identical to handed-down Zhangzhou ware were found at Hua’an in Zhangzhou. It confirms historical records that connect the ware with Zhangzhou.

My clock shows I have only 20 minutes left. The guards start to close out certain areas for visitors. As I have not seen all I run over to the area were kiln types are explained. The explanations given are:

a) egg-shaped (or cai) kiln long used in Jingdezhen and developed from the gourd shaped late Yuan kiln explains a lot.

b) The dragon-shaped kiln, mostly used in Southern China since the Shang (16th – 11th century BC).

c) The Mantou kiln (or round kiln) developed from the Shang period and which is a type traditional for the North of China. See the blue-and-white vase from the Xianfeng period (1851 – 1861 AD) and Daoguang (1821 – 1850 AD).

There is a fencai Jingdezhen revolving openwork vase from the Qianlong reign (1736 -1795 AD). And a Tongzhi reign (1861 – 1874 AD) plate - yellow with a green and a brown dragon and made in Jingdezhen.

Get started right away!

What are you waiting for? Capture your adventures in a digital diary that you can share with friends and family. You can switch between any of your devices anytime. Get started in our online web application.