Saturday October 22, 2016

Fuzhou, 22.10.2016

We know something about Fuzhou and its history: it is the capital of Fujian, located on the Northern shore of the Min river. The Fujian landscape is lifted by mountains from the North East to the South West. Agriculture is possible in the lower areas. The original name of Fuzhou is Ye (from Lya; literally: Beautiful); Ye became the capital of the Minyue Kingdom, when, in 202 BC, Emperor Gaozu appointed Wuzhu as King of Minyue. The year 202 BC has become the official founding date of the city of Fuzhou. Ever since, Fuzhou has a leading role in Fujian’s prosperity.

In 110 BC, the armies of Emperor Wu of the Han period defeated the Minyue kingdom's armies during the Han–Minyue War and annexed its territory and people into China. Many Minyue citizens were forcibly relocated into the Jiangnan area, and the Yue ethnic group was mostly assimilated into the Chinese, causing a sharp decline in Ye's inhabitants. The area was eventually re-organized as a county in 85 BC.

In order to escape from the wars in central China, many people fled from the West (265 BC –316 AD) and East (317 – 420 AD) Jin dynasties. Together with eight aristocratic families (Lin, Huang, Chen, Zheng, Zhan, Qiu, He, Hu), they fled to Min, in the South. These migrations from Central China brought about the crucial integration of the Northern Han into the Min area. Along with the many counties of Fuzhou, those of Ningde are considered to constitute the Mindong (or Eastern Fujian) linguistic and cultural area.

Fuzhou is a big city with about 5 million inhabitants plus 1.7 million inhabitants in the outer, rural areas. Today, for Fuzhou, the port for international maritime trade is a major source of income. There is a lot of trade here in rice, tea and oranges. The production of steel, industrial chemicals, textiles, paper and technological equipment, food-processing and commercial banking – are some of the major industries.

The bus picks us up and drives us to the Fuzhou Fujian Municipal museum on Wenbo road. The driver has his own way of driving through a huge city like this. He is from the Haka people: who, in China, are subject to discrimination.

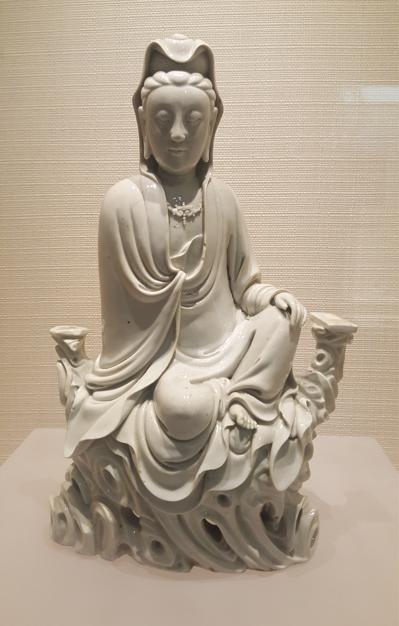

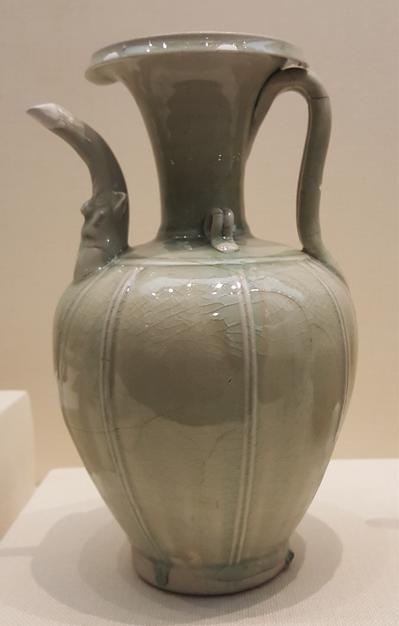

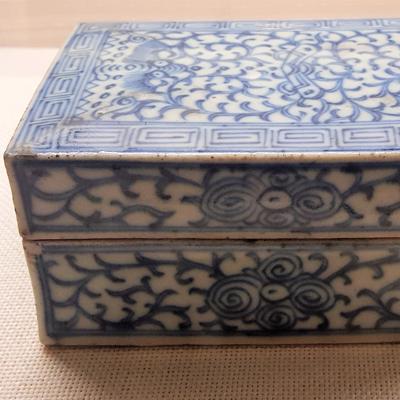

In the museum, we learn more about Southern Dynasty censers, inkslabs and Zadou vessels. I would like to have a guidebook or pamphlet to get more details. I buy a small book, but it has just two words in English: “Contents” and “Fujian Wenbo”. On the ground floor of the museum I find Carl on a bench, frantically typing on his smartphone. What he does is just what we all need to do: he is writing Chinese characters in a software program on this screen and pronounces words in Chinese. He remarks, that I make him lose points by disrupting his lesson.

The Tang celadon frog shaped pillow, however, is wonderful and does not need explanation. The same is true for the Ge wares, the Yuan jar – high quality again – all of it. Via a mirror, placed under the pots, we

see various marks on the pots indicating the period in which they were made.

We learn more about the Fuzhou trade from the info boards on the wall of the Museum: During the Han period, the Min Yue kingdom Fuzhou already started trading with Guangzhou, Vietnam, the Philippines. Taiwan and Japan. From the Jin to the Five Dynasties, people from the central planes were migrating in large amounts to Fuzhou, spreading culture and production technologies. During the Song, Fuzhou was famous for its shipbuilding capabilities, with the quantity of woods around it was never out of stock.

To increase the shipping and marine trade of Fuzhou the central government of the Yuan dynasty established another office called Wanhufu to deal with Maritime affairs in Fuzhou. Gradually Fuzhou became an important port city for transhipment of goods like Jewellery between China and foreign countries. In the Ming (1368 – 1644 AD) Dynasty Zheng He ushered the world with his voyages on the Western Seas into the Great Age of Navigation. Symbolizing China’s endeavour to embracing the outside world. Zheng He had chosen multi religious explorations and found a Sea route to Southeastern Asian countries. During both the Ming (1368 – 1644 AD) and Qing (1644 – 1912 AD) periods officials from Ryukyo would either visit Bejing via Fuzhou or would stay in Fuzhou for learning the culture of China. The result of the trade during the Ming was a spreading of China’s traditional culture to Japan and South-eastern Asian countries. In addition, Chinese ceramics and porcelain were bought in bulk quantities by the Ryukyuan. Also it was during the Ming that an office was allowed to be built in Fuzhou for the Ryukyu trade. Ryukyuan sailors received a special translator to report to the emperor, as well as send the decrees of the imperial court to Ryukyu. This opened the way for great Sino Ryukyu trade relations. For nearly two hundred years, the Ryukyu Kingdom would thrive as a key player in maritime trade with Southeast and East Asia. Central to the

kingdom's maritime activities was the continuation of the tributary relationship with Ming Dynasty China, begun by Chūzan in 1372 and enjoyed by the three Okinawan kingdoms which proceeded it. China provided ships for Ryukyu's maritime trade activities, allowed a limited number of Ryukyuans to study at the Imperial Academy in Beijing, and formally recognized the authority of the King of Chūzan, allowing the kingdom to trade formally at Ming ports.

The Chinese provided Ryukyuan ships traded at ports throughout the region, which included, among others, China, Đ?i Vi?t (Vietnam), Japan, Java, Korea, Luzon, Malacca, Pattani, Palembang, Siam, and Sumatra.

Japanese products - silver, swords, fans, lacquerware, folding screens - and Chinese products - medicinal herbs, minted coins, glazed ceramics, brocades, textiles - were traded within the kingdom for a long time against Southeast Asian sappanwood, tin, sugar, iron, ambergris, rhino horns, ivory and Arabian incense.

The British had first given Opium for free to the Chinese; then, when a lot of Chinese got addicted, they abused the trade to obtain goods like porcelain, silk and other goods - thus opening the Chinese

market, which had been closed for them. (In 1842, the Treaty of Nanjing forced the Chinese to keep the Fuzhou harbour open for international trade.)

Lin Zexu (30 August 1785 – 22 November 1850) was an administrator who rebelled and fought against the foreigners who imported opium via Fuzhou harbour. His name is connected to the Opium War; he is a big hero for the Chinese around the world (and for me as well!). He initiated the burning of opium which took place in Humen, a district in Donggua, from June 3 to June 25, 1839.

From 1861 onwards, Europeans started settling in Fuzhou; they built factories and exported tea.

The blue-and-whites are of the best quality, there is a great bowl from the shipwreck Wanjiao no.1, which went down in the Pingtan waters of Fuzhou (Kangxi period). The black glazed Song dynasty cup has an intense glaze.

Since 1666 the Dutch East India Company exported tea to Europe. Fuzhou was the first city, in 1684, to levy export duties in China.

Since the Song, jasmine was mainly produced in Fuzhou. The tea business is still important for Fuzhou, especially the trade of jasmine tea. Tea trees grow between the rock layers, in the shade on the Drum mountain. This tea is called Bo Yan Cha (cypress rock tea), which was was very popular during the Ming. Another famous tea is

the Fang Shan Lu Ya tea, produced in Shanggan Town, of Minhou county.

Fuzhou was one of the five ports designated for international trade in the Treaty of Nanjing (see above) – which was a disaster, since the Opium trade started to flourish because of it. When the old tea road (from Guangzhou to Fuzhou) and the new road (from Fuzhou to Shanghai) were cut off, due to Taiping movement rebellion, the Qing emperors started to export tea from Fuzhou. It became of the three largest tea markets in China, later in the 19th century, it accounted for 1/3 of China’s tea export.

From 1861 onwards, Europeans started settling in Fuzhou; they built factories and exported tea.

This museum is indeed a good place to improve our understanding of the history of Fuzhou! The history explains about the sea going Fuzhou people, their inventiveness and strength. Traders in heart and soul, what adventures they must have lived through on the rough seas! The historical events provide a stark contrast weith the fine porcelain displayed in the vitrines.

There is a very special brown glazed eggshell pottery jar. More Wanjiao no.1 porcelain is shown, so gorgeous. Lots of figurines,

Neolithic pots, explanations about the Minyue people. Hard pottery Zun-vessel from the Shang and Zhou dynasty from the Huangtulun site. I feel good here! The celadons are always so lush; the calming serene greens are very natural, without no cracks. (Green is such a difficult colour to paint with: it can be too overwhelming on canvas; on pots however, it is subdued.)

Only too soon we need to leave the museum; the bus waits for us to takes us into the city. We have to choose: go shopping in the commercial Sanfangqixiang zone, which has been rebuilt into a shopping street of the 19th century – or: go to a temple: the Xi Chanzi temple of Fuzhou.

Go to the temple of course! At least, that is what I want. The archaeologist, however, firmly states to me that she is not the guide. That we should go to the commercial area; I get a bit upset with this archaeologist. She fiercely adds "Professor so-and-so says: "go to the shopping area". Compared to visiting a temple am advised to go to the market. A lot of my books at home are Taoist. Am 15 hours by flight from home.

The group gets into debate on the sidewalk. Now the bus driver drives off.

(Next day in the bus, I overhear a member of our group say: “Oh yeah, we went for lunch with the archaeologist. She admitted to us during lunch that the commercial district and shopping area was nothing and not worthwhile at all”. Oh well, group travel! Luckily I discovered the museum of Lin in the afternoon. Something good did happen!).

The afternoon is hot, I walk through the busy street of the commercial area alone. The small shops are advertising their wares. It is Saturday afternoon and very crowded. Some old are houses refurbished in old style. There are good expositions of handicraft wares too. I encounter Ting-tiang, Wei Lan, Marion and Sam in one of the exposition spaces. But I decide to move on without them. At a bakery and cake house I buy very fresh cookies; fresh is the pastry and dough, and the cookies do not contain a lots of sugar. I try to get money from the ATM. As it takes very long before I get my card back from the ATM, a nice lady in the queue, explains this ATM is not working - that I should go to an ATM elsewhere. She offers me a ride on the back of her scooter, which I gladly accept.

Sitting at the back of a scooter going through traffic, holding a plastic bag with fruits, I feel like a real Chinese citizen.

Too soon we arrive at the other ATM. I wave goodbye to the very kind scooter lady who got me here. Continuing my path back a Mosque, which I had passed by before this adventure, I find it hidden behind big walls in a neighboring street. It happens to be the house of the great hero Lin Zexu, the administrator who rebelled, negotiated and fought against all countries which imported opium via the Fuzhou harbor. This house of Lin Zexu’s is located in Fuzhou's historic Sanfang-Qixiang ("Three Lanes and Seven Alleys") district; it is open to the public as a monument and also houses an anti-drugs museum. Inside, there are objects and explanations on his work as a high government official. His fight against corruption and opium helped the emperor realize what a bad deal it was to negotiate with the English, The opium bought from the British by him was ordered to be cut up and put in trenches on the Bogue river side in Canton. His efforts to improve agricultural methods; his campaign to save Fuzhou's West Lake from becoming a rice field: all is very well documented, even though in Chinese.

I walk through the small courtyards, under balconies and stoa: there are palms and Bonzai in pots and rusty canons from the Opium war times. The museum against drugs is shocking, there are pictures

showing it destroys the teeth in your mouth, your heart and your soul; whole communities go down because of it. What better way to combine the truth at this location with the statue of our hero Lin Zexu? I make a deep bow before the statue of this noble man and put yuans in a big pot to support the museum. It is still and again very hot and humid today. Many people want selfies with my sweaty face on it again. Am surprised by their questions for photos as my English looking freckled skin may remind them of the English oppressors. In any case, I keep myself as humble as possible, an extremely shy mouse in a garden full of butterflies: the Chinese people.

Carl strides unto the court of the garden with his linen bag with a big red fly on it. We sit down in a court yard and eat cookies from the paper bag. Carl eats his cookie, politely chewing. Chinese families with small kids jump around us. It remains a little hot. So nice to sit for a short while in this courtyard and absorb the atmosphere.

We do feel terrible about the Opium wars and the drugs. The drugs museum has left a massive impression on me, and in the heat emotions rise higher than usual. One line in English on the wall says; “You may have never touched hard drugs, but you must honestly learn how to stay away from it”.

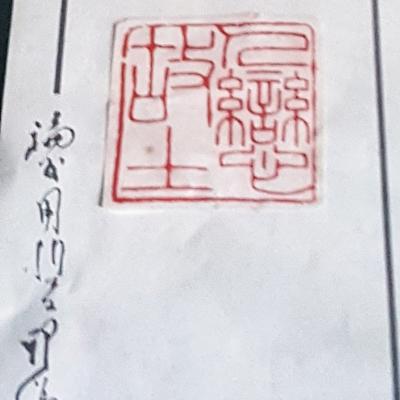

I leave this important place, as now I go explore the commercial and renovated Three lanes and seven alleys district. In one of the alleys I

find a tiny museum with stamps and seals exhibited. I am the only one attending this house. A man at the reception is asleep, but when I get in, he wakes up in the haze of warmth, darkness and dust. He looks at me in a melancholic way. Together we admire the stamps, splendidly carved, and we listen to a song playing on the radio. He puts on the light for me. No English texts to explain what the stamps are all about.

Next to this museum is a square where schoolchildren play. I sit down on a bench there for a while, admiring the spirit and happy energy of the kids. They are running like crazy hares around the square! I cannot move, feeling it is far too hot to move around like that! Some come to have a look at my eyes. We do high fives, and make fun.

In the late afternoon, I buy some “hippie dresses” from a small store. The sizes are just about right for me, everything more or less fits. The shopkeeper shows me other lovely dresses, and a top with coloured beads. I pick some of those and negotiate a price. She looks closely at the freckled skin on my arms. Kids stick their heads around the curtain of the dressing room. I feel lucky having ended up here; the soft female atmosphere is just perfect. In Moby Dick, Ishmael says: “I stuffed a shirt or two in my old carpet bag”, - so when will I learn to

live as frugal as he did? Wearing this lighter stuff at dinner in this humid weather will be nice though. Walking back to the Hotel at dusk around 17 hrs. I learn a lot from exploring the small streets in the direction of the lake. Families live in tiny shops, the lingerie store offers push up bra’s for 8 Euro. There is a book store, which (I am used to it by now), sells only Chinese books, with again the English word: “Contents”. This Sanfangqixiang area has more temples, galleries and pavilions, craftman’s shop and courtyards with such beautiful Bonzai. This shopping street at dusk looks like Hiroshige’s wood block print: “Night View of Saruwakacho”.

Our hotel is located in a great place overlooking the lake. In the small streets I leave behind there are no trees; the air is certainly not healthy, folks will die from this dirty air. The overcast skies of dusk are covering us, the colors are soft, but how would it look without SMOG here?

After a shower in the hotel, I run downstairs and see the group. I follow them along the lake. We see couples dancing; the moon looks at us. In a private room in the restaurant we are seated at a big round table in a private room. ``the spirit is high as usual, we drink wine and have great food. Through my eye lashes I watch the guests in the other rooms. The overall atmosphere is very good here.

Tonight Bente has stayed in the hotel; we miss her at the table. She is

the only one in the hotel who has a “room with a view” - on the lake that is. Truke and I are making jokes again; Carl pours wine; Sam roars and talks about Woucai porcelain; Marion makes fun; Wai Lan orders the best food; Ting-tiang looks after us; Christine makes plans - another fabulous evening together is being celebrated.

On the way back to the hotel, music plays loud on all squares along the lake, couples are dancing again. Ting-tiang and Wai Lan now take the dance floor too, so romantic! Under the Fuzhou sky, at the lake with its glimmering lights in the dark, I ask a Chinese man if he wants to show me how they dance. In a moment he grabs my arm and we almost fly over the dance floor under the open sky - he is a star dancer. I try to follow into his steps.

Continuing our path, Truke tells lively stories to me, before and behind us is our group. The indigo night is around us; we are so lucky. There must be a contradiction in my life – just compare this to my serious work at IKEA and other multinationals, with bits and bytes,

servers and routers, clouds and computer networks; - and combative, bullying tribes of male managers! Back in my room I get some nice music out of my smart phone. It is paradise here!

Get started right away!

What are you waiting for? Capture your adventures in a digital diary that you can share with friends and family. You can switch between any of your devices anytime. Get started in our online web application.